Pasture Management for Wood Pasture and Parkland

Managing the land around the tree is just as important as managing the trees themselves.

Open pasture

The structure of the site, in particular the balance between tree’d areas and open pasture, will influence all aspects of the habitat itself. It will affect the shape and potential lifespan of the trees, the species that will live in them, the available forage and the fungal diversity to name but a few.

On sites where grazing has lapsed or been too light, you may need to release veteran trees from encroachment by other tall growing trees and scrub. Open grown trees rely on the presence of open habitats to reach their full life expectancy. Over shading not only reduces the trees suitability for many rare species, but it also hastens their decline through old age, a stage we’d ideally aim to prolong.

Grazing

Wood Pasture and Parkland is a characteristically open habitat, although as varied mosaic habitat it may also incorporate some areas of closed canopy woodland as part of the site. To prevent scrub encroachment and succession to secondary woodland, the area of wood pasture and parkland will have to be managed to maintain this structure. Preferably this will be through grazing, but in areas where this is not an option, regular mowing can also achieve the same outcome.

With appropriate grazing animals at the right time of year (usually summer and autumn when the ground is not too wet) and at the right stocking levels you can achieve a balance between open areas, old trees and scrub.

Grazing is the key to getting the right balance. Enough to keep open areas but not too much to cause damage to the soil and trees and allow scrub to develop. If grazing levels and timings are right you shouldn’t need to provide extra food which adds nutrients to the grassland, damaging both fungal and plant diversity.

Grass managed with appropriate grazing levels will have a patchy or tussocky structure. It will have areas of longer grass and areas of shorter grass.

Scrub

The invertebrates whose larvae live in wood decay inside old trees also need food sources for the adult stage when they emerge. This may be provided by nectar on flowering scrub species. Ideally, a site would have a a range of different species which flower at different times throughout the year. Willow catkins provide early spring forage followed by hawthorn in May then cow parsley, hogweed and bramble, then ivy flowers which flower late and will feed insects right into November.

Too much scrub is not good, but it should be present, scattered across the site. Thorny scrub can protect young trees from grazing animals while they establish.

If your site is low on scrub, consider fencing off an area to protect it from grazing animals and allow it to develop into a dedicated scrub patch. Interpretation boards are a good way of explaining this to visitors if your site is open to the public.

Soil care

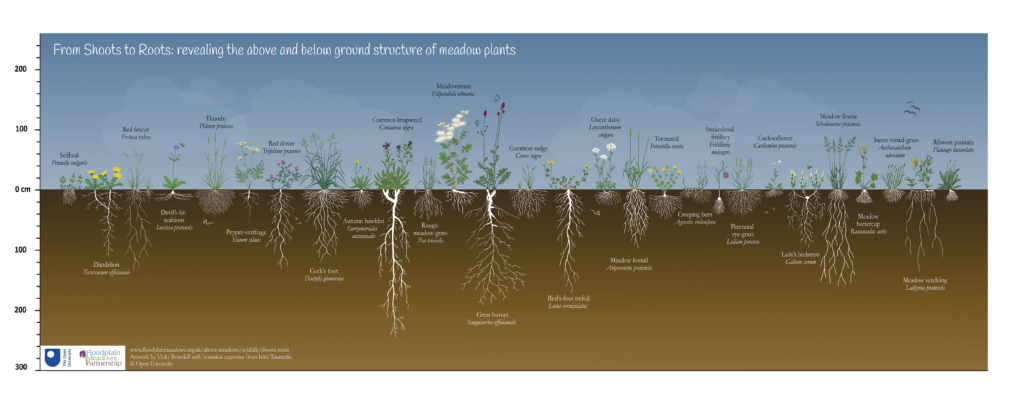

It is important not to plough the grasslands wood pasture and parkland, especially where ancient soil structures still exist. They contain thriving fungal communities that help the trees gather water and essential nutrients. The result of not ploughing is reduced soil erosion and less damage to fungal hyphae networks. Whilst some plants thrive in disturbed soil there are others that prefer this undisturbed soil structure.

Fertilizers contribute to the loss of both plant and fungal diversity in grasslands. Specialist woodland and meadow wildflowers are often adapted to thrive in nutrient poor soil in some cases this means the addition of fertilizer is directly toxic to them. Similarly, supplementary feeding animal stock increases the nutrient levels in the soil and so also decreases the quality of the grassland for wildflowers. This can also impact the precious associations between tree roots and the fungal networks.

Soil compaction can create anoxic (lacking oxygen) soil conditions that alter the habitat and reduce the number of species that will live there. Ultimately compaction will lead to the stunting and even death of the grass, damage to tree roots, and damage to soil fungal mycorrhiza that are associated with tree health. Compaction of soils on wood pasture, and especially parkland that have heavy footfall, is likely around pathways and infrastructure. Compaction in areas that are not pathways can indicate overuse of a site, or under-management of this risk. Evidence of compaction can include bare soil, permanent tyre tracks and ‘ponding’, where water permanently settles due to the reduced permeability of the soil.