Case studies and restoration

This page aims to provide examples of wood pasture and parkland sites that have, or are currently undergoing restoration.

Our latest case study

Sustaining the unique cycle of life in Robin Hood’s forest

The adjoining nature reserves of Sherwood Forest and Budby South Forest, in north Nottinghamshire, offer the visitor a continuum of varied wood pasture types, comprising denser canopy woodland and lowland heathland with scattered open grown trees across 1,000 acres, managed today by the RSPB.

- + Read more: Sustaining the unique cycle of life in Robin Hood's forest

Not only is Sherwood internationally famous for the legend of Robin Hood, but it has Europe-wide importance for one of the largest assemblages of Ancient Oak trees across the continent.

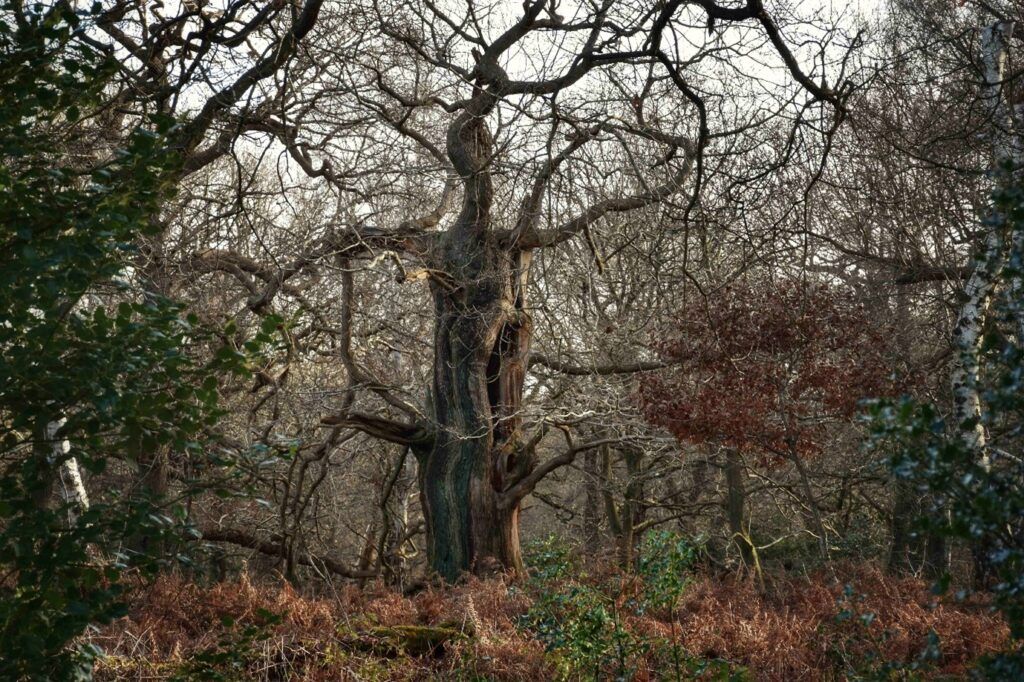

A mix of birch, oak and scrub in Sherwood Forest. Photo by Tammy Herd. Among thousands of oak and birch trees (the historic name for the area is Birklands, which is Old Norse for Birch Wood) there are around 400 living ancient oaks within the forest, according to a 2023 independent tree health survey, with many more standing dead oaks (hulks), which have provided a vital habitat for saproxylic invertebrates here for millennia.

Saproxylics are invertebrates which depend on decaying wood for all or part of their life cycle. Among the species found in Sherwood and in few other locations across the UK are the cardinal click beetle, Welsh clearwingand Teredus cylindricus.

Teredus cylindricus photographed in Sherwood Forest. Photo by Alex Hyde. The RSPB is working at Sherwood and Budby to prolong the already incredible lifespan of the reserves’ ancient trees and to close a ‘generation gap’ which threatens the succession of saproxylic habitat which is provided by the ancients.

History

Sherwood Forest has always been a managed landscape since humans settled in this area.

Rootling by wild boar and browsing by deer for centuries, along with grazing of livestock, not to mention the harvesting of timber for construction, ship-building and fuel, have shaped its character. But so have the many years as a royal hunting forest, subject to strictly enforced laws on its use, and, later, as part of a ducal estate.

Visitors pose next to the Major Oak in the early 20th Century. Credit North East Midlands Photographic Record. Tourism, fuelled by interest in the legends of the outlaws and the iconic Major Oak tree, have also had a profound impact on the forest for over two centuries, while Budby South Forest was a military training area for several decades until the early 21st Century.

Managing the reserves

The RSPB has set a 500-year ecological ‘tree-time’ vision for Sherwood and Budby to optimise its habitat value for birds, insects, fungi, plants and mammals.

This is not a landscape which can be simply ‘left to nature’. A range of interventions have been brought in to restore the wood pasture here to favourable condition.

These include the revival of livestock grazing with English Longhorn cattle, a rare breed which is both hardy and docile, and one that both grazes the understorey and browses low-hanging leaves.

English Longhorn cattle in Sherwood Forest. Photo by Paul Cook. Their wandering through the enclosures helps to control species such as bracken, which can, if left unchecked can dominate and suppress other vegetation.

Through the winter, Hebridean sheep will be brought on the heathland of Budby to graze the sward more closely.

Supporting the forest’s elderly residents

Central to the management of the reserves is how the RSPB and its partners protect the ancient oaks.

A Sherwood ancient oak. Credit Tammy Herd. An oak is regarded as ancient when it reaches 400 years, by which time it will have acquired many of the veteran features which create the ideal conditions for saproxylics to thrive.

The decaying heartwood of the ancients is ecologically-rich, and each tree is effectively a nature reserve in its own right, supporting an estimated 2,300 species.

However, the harvesting of timber in previous centuries has created the generation gap between the forest’s oldest and younger trees.

The priority is to prolong the ancients’ already phenomenal lifespan, while taking a radical ‘no regrets’ approach to closing the cap using a technique known as veteranisation on younger oaks.

What is veteranisation? Throughout the winter, RSPB staff, volunteers and specialist contractors ensure that the light and space-hungry ancients are provided with the conditions which will sustain them.

Halo veteran oaks This can involve haloing – removing younger competing trees from around an ancient – or aerial pruning to create space for light to reach the forest floor or to prevent premature collapse of limbs.

Where an ancient shows signs of its trunk splitting, the structure has been retained with the use of metal bands or strapping. This ensures it remains standing and holds the decaying ‘red rot’ habitat that saproxylic species seek within it.

Having a mix of standing and lying dead or decaying wood is something that is lacking within British wood pasture, but it is vitally important as the two types attract distinct suites of species to colonise them.

Visitor pressure

Sherwood Forest is an ideal place for many people to forge a lasting connection with nature. Drawn by the legends of Robin Hood and the sight of the magnificent 1,100-year-old Major Oak, the forest welcomes approximately 350,000 visitors from across the world.

With Sherwood previously managed as a country park by Nottinghamshire County Council, it is an open site, accessible at all times of day and night.

This ease of access brings additional pressures on the ancients, particularly the temptation for people to get too close to these incredible, yet fragile living sculptures.

Walking over the root plates of the ancients, causes the sandy acidic soil to compact, reducing the quantity of moisture and nutrients which penetrate the ground.

Dog waste alters the composition of the ground flora and particularly the epiphyte species which can be found at the base of the ancient trees. Dogs also cause potential disturbance for ground-nesting birds, so effective messaging around controlling pets is essential.

The use of fencing and natural dead-hedging or brash, combined with key messaging, is intended to encourage visitors to admire these fabulous trees from a respectful distance.

Analysing outcomes

The success of these interventions will ultimately be realised decades or even centuries from now.

However, we can already point to encouraging evidence of the colonisation of veteranised trees by invertebrate species.

Working with expert entomologists, the RSPB has used ‘vane trapping’ – a standard methodology for intercepting invertebrates – on trees which were veteranised at least two years previously.

Vane trapping on veteranised trees in Sherwood Forest. We are already noting the presence of darkling beetles and other saproxylic species, slime moulds or other organisms which take root in the exposed heartwood, as well as ‘exit holes’ bored into the trunks and limbs of the trees.

Monitoring will continue over the years to come, assessing how the veteranized features have attracted the species we need in Sherwood to ensure the succession of its ecological cycle.

This should make a vital contribution to the survival of this world-famous forest for future generations to enjoy, understand and protect.

Major Oak in Sherwood Forest. Photo by Rob James. Written by Rob James, RSPB Communications Officer

- + Diversifying the sward at Windsor Great Park

Diversifying the sward at Windsor Great Park

Parts of Windsor Great Park support species rich grassland on ancient soils, which have been spared the plough and treatment with fertilisers and chemicals. However some areas in the north of the Deer Park were previously farmed as arable, and reverted back to permanent pasture many years ago. These areas are now semi-improved grassland but with a rather species poor sward, with few herbs of conservation interest other than some Bird’s-foot Trefoil. In spite of being ‘organically managed’ such areas are not naturally developing any significant flower interest, and it was proposed to enhance these using the ‘green hay’ method, using local Windsor seed from flower rich areas at nearby Stag Meadow. Part of the motivation to do this was to increase the amount of native flowers in our grasslands, but to do this in areas of the park with old trees will hopefully provide improved nectar sources for the insects that use the old trees.

Stag Meadow – this area of species rich lowland meadow is the donor site. Most of it is usually cut for hay. It did not affect the hay harvest to use some areas for green hay.

Green hay Prep1 – the grass was cut short and arisings removed. Then it was scarified with a chain harrow to open up some bare soil. The first trails were done in 2022, not especially helped by the extreme heatwave. In early July, 4 areas of about 0.5 ha were prepared by mowing grass very short and removing the arisings. Then the ground was scarified with a chain harrow to open up some bare soil. In mid July the hay was cut and loaded up into a Muck Spreader.

Prepared ground – showing the parched dry grass (from 2022 heatwave) and plenty of bare ground. We had planned a later cut to allow more diversity of seeds to ripen, but by mid July the hot weather had led to the grassland becoming a fire risk (close to many ancient and veteran trees). It was spread over the 4 areas. The red deer herd have constant access to these areas, and they do graze and loaf on them. It was always a risk that deer grazing might restrict flowering, but as flowers (such as harebell, heath bedstraw, heath speedwell, tormentil) are able to flower in other parts of the deer park we thought this ‘worth a try’. We decided not to fence the plots off but that might be an interesting variation on this sort of work.

Spreading – The cut green hay was spread using a muck spreader. Seedling establishment was at the mercy of the weather and deer behaviour, but by late winter it was clear that there was a lot of germination of broad-leaved species. A walkover survey in July 2023 showed significant establishment of Common Knapweed, with quite a lot of flowering. Other forbs present include Oxeye Daisy, Sorrel and Red Clover. As such early results are encouraging and I think that there will be an increase in species and flowering in 2024. We have other areas of species-poor grassland around the Great Park to enhance and we plan to do more green hay spreading this year and beyond.

Des Sussex

thecrownestate.co.uk - + Ullswater and Troutbeck valleys

Wood pasture restoration and creation in the Ullswater and Troutbeck valleys

Area restored: 640 ha

Start and finish date: 2015–25

Why?

Cows and Trees is a landscape-scale project to restore and enhance wood pasture habitat on National Trust land in the Ullswater and Troutbeck valleys in the Lake District. Wood pasture is in decline and recognised as a Priority Habitat for conservation, and these valleys have some particularly important sites, largely on the old deer parks at Troutbeck Park Farm, Glenamara Park and Glencoyne Park. Veteran tree surveys have identified about 750 veteran trees on site. The overall aim of management is to reduce the sheep grazing pressure across the farms and entirely from the wood pastures. We shall rely on natural regeneration processes in the wood pasture areas, rather than tree planting, with the exception of native crab apples propagated by our Plant Conservation Centre from locally collected fruits.

There is support for this project through the Higher Level Stewardship. Our conservation grazing plan is to:

- Reduce sheep numbers from approximately 4,000 to about 1,900 which represents a fall of over 50% and gives a new stocking density of 0.75 sheep per hectare.

- Wood pasture-type prescriptions over an area of 745ha which represents 30% of the farmed area. The wood pastures will be grazed by about 90 cows/ponies at a stocking density of about one animal to about 8ha.

The aim of the project is to work in partnership with our tenants to demonstrate sustainable land management on a landscape scale where there is a reliance on natural processes. Although this work has been agreed through the HLS system with its 10-year window of funding, all of these prescriptions have been the basis of the new farm tenancies. Therefore, it is expected that this management will continue beyond the life of the scheme although there will be a challenge to work out a way to support it. Key to this will be targeted monitoring to record change and adjust prescriptions as required.

Other works associated with this project include:

- The rebuilding of 500m of ancient deer park drystone wall

- 5,000m of new fencing to secure the wood pasture boundaries and an additional 4,000m of fencing to create a river corridor

- Felling of 12ha of non-native conifer woodlands

- A new 2.2km footpath through Glencoyne Park to allow public access to the park and Aira Force waterfall which has been supported by a grant of £80,000 from Natural England

Results so far?

- This work is essentially about giving the land a rest and a chance to bounce back so very early days yet. However, the sites feel more plentiful (right word?) and a recent NE SSSI monitoring visit to Troutbeck Park was very positive about the changes in vegetation – instinctively feels right but part of the excitement is watching what happens next. .

- The obvious indicator of success will be new tree regeneration but perhaps as important will be the development of a more robust and herb-rich grass sward that is better able to absorb water. This should help with climate change and the expected increased ‘flashiness’ of rivers. This latter point is really important in Ullswater which was particularly badly hit by Storm Desmond – there is a community flood group looking at long term and short term solutions to slowing the flow and this work is very much part of the solution.

- Cows exploring the site widely, covering a huge area and thriving

Extra tips

- Don’t treat future monitoring as an add-on as it’s too easy to forget (we haven’t got it right yet) We now have a monitoring regime in place that has covered veteran trees, lichens, birds, tree regeneration and vegetation change so a fairly robust baseline to measure future change.

- Try to get the details of these schemes right at the outset as they can be very restrictive and hard to change in the future

- To work, these schemes need good tenant buy-in to carry out the management on the ground – simple things like tenants keeping sheep out of wood pastures which is no easy task with Lakeland herdwicks!

- Get in quick with contractors as there is a huge amount of this work going on at the moment and good ones get booked up early

Further information: John Pring, Countryside Manager, National Trust

- + Loweswater

Loweswater

The 7 acres of wood pasture at Loweswater was purchased by the current Landowner, Liz Crocombe in 2019 when it came up for sale. Liz is a very keen conservationist and couldn’t resist the opportunity to save the wood pasture and surrounding oak woodland after having to watch it slowly demise for the last 20 years. Despite being an area of registered ancient woodland and within a stewardship scheme, the wood pasture and surrounding Sessile Oak woodland was in a degraded state because of long-term overgrazing by sheep, widespread tree felling, and removal of all the deadwood. Apparently, this had been going on for years, and was the log supply for the local pub!

Old maps from the 1890’s show the wood pasture to be present under the name Gill Carr, suggesting historically it was even wetter and contained more Willow than it does today. There is evidence of drainage channels in the wood pasture, as well as the watercourse (Gill) being moved, which appear to have been done for the surrounding Sessile Oak woodland. Presumably, there were grand plans for the wider woodland to be a charcoal coppice woodland, but it never happened, possibly due to the difficultly of the terrain and collapse of the charcoal industry.

Despite the poor condition in early 2019, it was clear this was a very special habitat. Several very large crowned Sessile Oak trees were still standing, and despite overgrazing, the grassland within the wood pasture was a mosaic of unimproved marshy and acid grassland. Throughout Spring and Summer 2019, we rested the land completely from grazing, just to see “what pops up”, allowing all the wildflower species time to grow up and make themselves seen. I carried out a botanical survey of the wood pasture in early July, and recorded 90 species of wildflowers. The highlights were Heath-spotted Orchid Dactylorhiza maculata, Devil’s-bit Scabious Succisa pratensis, Pale Sedge Carex pallescens, and the endemic Montane Eyebright Euphrasia officinalis ssp. monticola which is a very rare wildflower restricted to a few upland grassland sites in the Lake District and North Pennines.

The birdlife was equally spectacular. By April, every tree had a male Tree Pipit setting out a territory, parachuting from the top of the canopy whilst in full song, into the grassland below. By May, the Pied Flycatchers and Redstarts had returned. To our delight the wood pasture turned out to be the battleground of several Cuckoo’s territories. I had seldom seen Cuckoos, mainly just hearing them, but here there were often 3 or 4 flying between trees either squabbling with each other, or being mobbed by the Tree Pipits. The wood pasture was alive with bird song from dawn until dusk, and became a magical place that felt a million miles away from the modern world.

With such a rich, important flora and birdlife, it was clear the wood pasture needed careful grazing management for these species to thrive.

Eyebright in particular is a fussy species that can die out very quickly with under grazing. Any grazing between May and July would have destroyed Tree Pipit and potentially Cuckoo eggs. In Late Summer 2019, after all the wildflowers had set seed and birds had fledged, we introduced some Cattle to graze back the years growth. The target structure by the end of the grazing period is to have some areas of short, well-cropped grassland, with longer tussocks dotted around and the occasional patch of denser vegetation for insects and small mammals to hide away in. By October the cows had done their job, and the wood pasture is once again allowed to rest.

Despite a very successful year for the bounceback of wildflowers and birds, the one thing in the wood pasture that wouldn’t be restoring itself any time soon are the trees. There is a fairly heavy population of Roe Deer, and that combined with the Cattle grazing has meant any natural regeneration is soon grazed off. The trees are particularly special in the wood pasture as they are grand, with huge domed crowns and canopies. However, there are only about 8 of them left in healthy condition, and all are of a similar age and structure (roughly 200 years old). There are at least 2 dozen stumps of felled Sessile Oaks within the wood pasture.

We need to get the next generation of trees up and running, and the only way to do that in a grazed wood pasture is through tree cages. This Winter we have just added 25 tree cages with support from the Woodland Trust and Cumbria Woodlands, and these will be planted up with about 50% Sessile Oak, but also a good diversity of other species. Alder, Downy Birch and Goat Willow in the wetter areas, and Crab Apple, Wild Cherry, Bird Cherry and Silver Birch in the well-drained areas.

There is a large time gap to bridge between the old and new trees, but, with time, the next generation will be well on their way, and hopefully in another 100 years, the wood pasture will still be as vibrant and alive with wildlife as it is now. Without Liz, the fortune of this site could well have been very different. 8 felled trees later and this would have just been open grassland. Some herbicide and fertiliser and it would be transformed to improved agricultural land, with the trees, wildflowers and wildlife a distant memory. Thankfully things are in place so that never happens. We now have a long-term management plan in place, and lots of ecological parameters are being monitored annually so we are able to see how the site is changing. g

Rob Dixon

Conservation Ecologist, Wild Lakeland

- + Coniston wood pasture restoration, South Lakes

Coniston wood pasture restoration, South Lakes, National Trust

Wood pasture is traditionally found throughout the Lake District where it provides a link between the wooded valley bottoms and open fell tops. This habitat is under threat from high grazing levels, causing a lack of natural regeneration of trees and many sites are becoming isolated islands.

Over 4 years the National Trust has been working with Natural England and other partners, to restore 200 hectares of remnant wood pasture; 70 ha at Coniston Wood and 130 ha at Tilberthwaite.

There were three main actions to restore this area:

• Re-wetting peat bogs (mires)

• Planting new trees and shrubs

• Implementing a new low intensity year-round grazing regime with belted GallowaysWithin this project the National Trust trialled new approaches to mirror natural processes and to reduce their impact on the environment.

Find out more in the video below: