Spotting urban mammals

Read our top tips for mammal spotting to help you take part in the Living with Mammals survey

Thank you for your interest in helping wildlife by joining in our survey. Don't worry, you don't need to be an expert and with the advice below you will be able to locate and identify species and recognise the signs they leave behind.

Where and when to look

Some of the best places to spot mammal signs are along features such as walls, hedges, fences, grass verges or field margins, that provide cover.

Mammals are typically nocturnal or crepuscular (active around sunrise and sunset, during hours of twilight). The best time to spot mammals is early morning, when it is quiet (without the human bustle that persists in towns and cities through the evening) and, as the light improves, there is the opportunity to observe still undisturbed tracks or other signs.

Field notes or sketches are a good reminder and sharpen observation skills. If you take a photograph of a field sign, include a coin or a familiar object in the picture to indicate its size. Recording the location of field signs on a map of the site, too, can tell you about an animal’s movements over time.

Who’s who

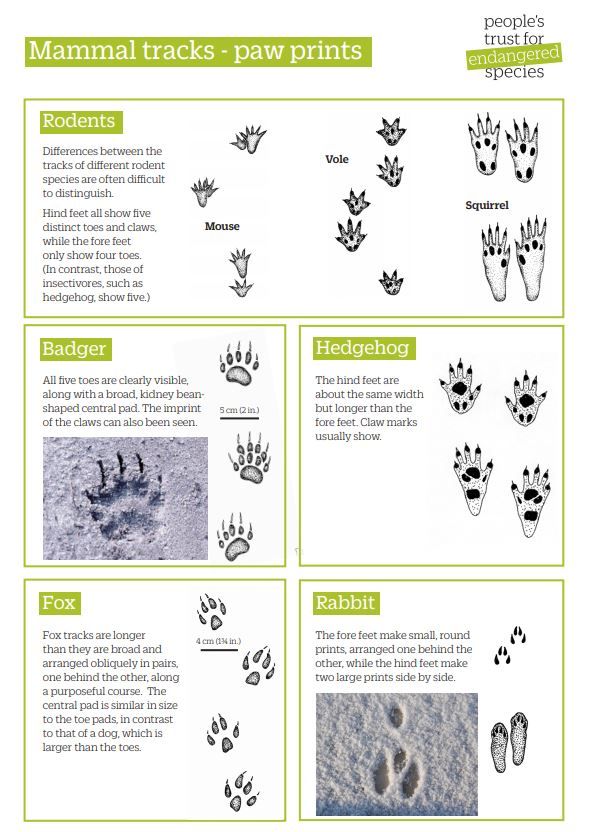

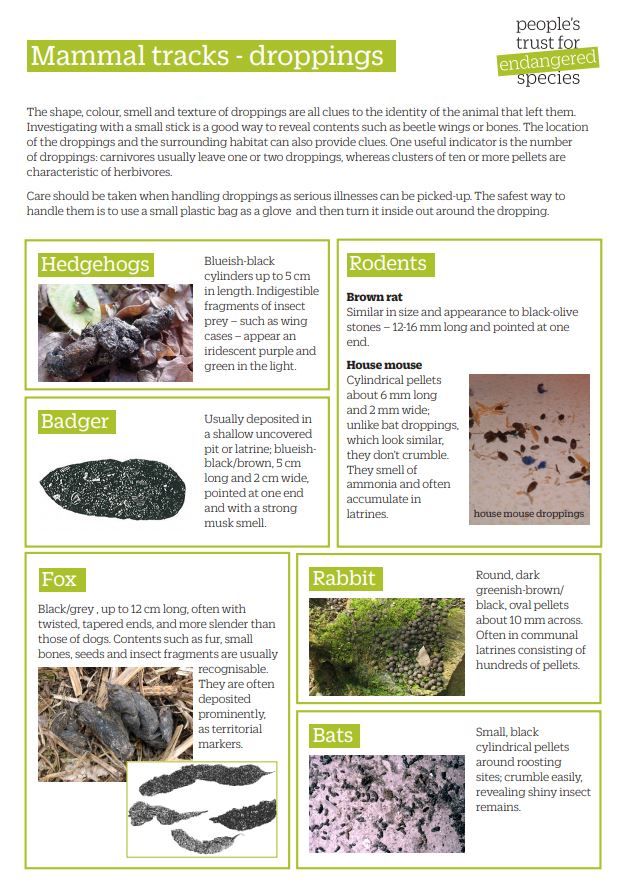

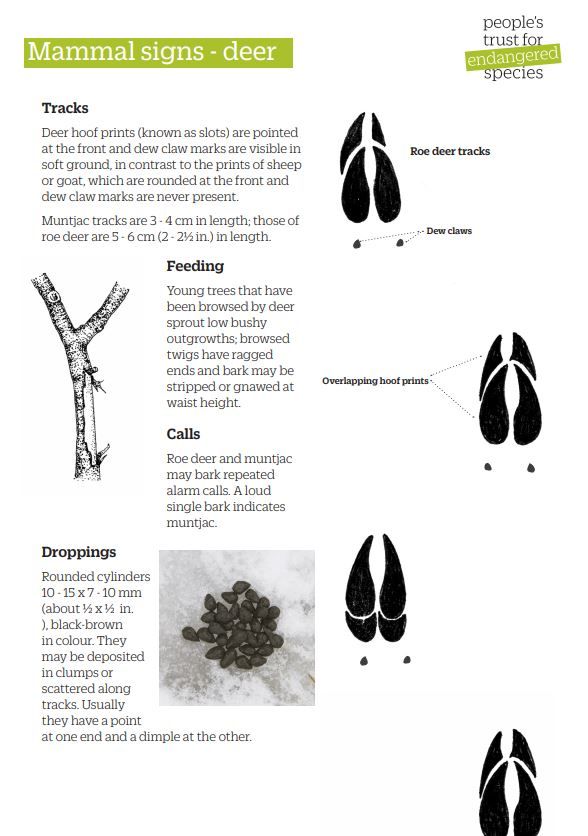

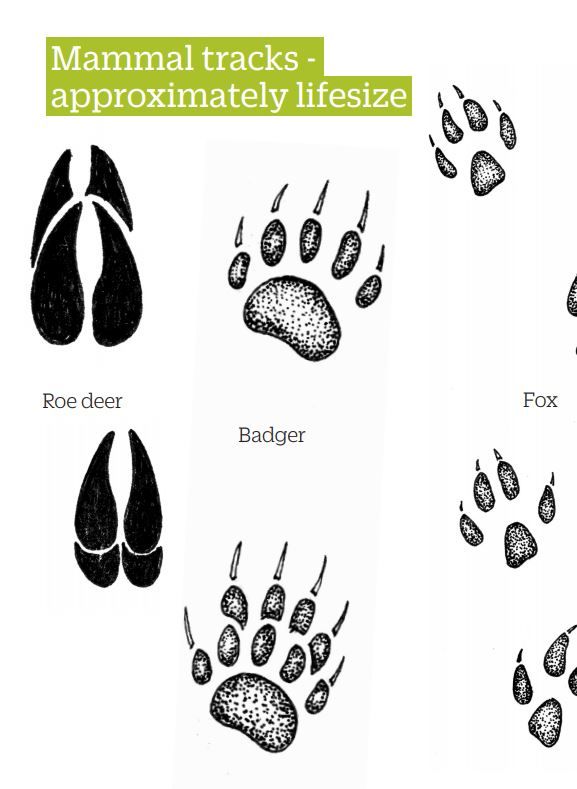

Recognising mammals can be straightforward—the bushy tail of a fox, the spines of a hedgehog or black and white markings of a badger are easy to identify—but for animals out and about during the early hours or at night, a sign might be the only clue. Use our handy guides below to help you work out who’s who.

Take a look at our mammal fact files to learn more.

Wildlife cameras

A fifth of gardens are home to grey squirrels, foxes, mice, voles, hedgehogs and bats, but over 40 species have been recorded in surveys of gardens.

Even with the patience and keen senses of a mammal detective, spotting wild mammals is an unpredictable business. Most are active at twilight or during the night and are careful to avoid detection by other animals on the lookout, such as owls and domestic cats. The best chance of observing a wild animal is often when you’re not there – so a camera set up to take pictures automatically, can be a useful addition to the mammal detective’s kit. Trail cameras (or camera traps) are sturdy, waterproof and self-operated, and can record digital still photographs, video or time-lapse. Their use to record garden wildlife has increased in popularity as the technology has become cheaper and more accessible, and they can be an excellent way to get to know who your wild neighbours are. For most uses, a 8 MP camera with infrared (IR) is suitable and will cost £100.

Location

Most trail cameras are triggered by movement and a change in ambient heat. The sensitivity of the detector can be adjusted depending on what you want to photograph and the location. Good sites to position a camera can be looking the base of a fence or hedge; near to the location of field signs; or in front of a feeding station. If cameras are too low to the ground, however, the size of the ‘detection zone’ is a lot smaller (and the camera is triggered by animals only in an area close to the camera) and images can look ‘burnt out’ or ‘bleached’ because too much of the flash is reflected back.

Type of flash

One of the features to consider when choosing a camera is the type of night-time flash. The nocturnal habits of many mammals make it necessary to use either a visible (white) or IR flash and, depending on the particular spec’ of a camera, either may be used. A white flash allows colour photographs to be taken, day or night, and provides the best quality images. The disadvantage is that it will scare away your subject. Infrared light is invisible to people and other mammals, and cameras with IR flashes {‘black LEDs’) are less obtrusive, but night-time images produced with these are in black-and-white. ‘No glow’ IR flashes are completely invisible, while ‘low glow’ IR flashes can be seen if viewed directly (although are much less bright than a white flash). The latter, however, illuminate a greater distance.

From gardens to neighbourhoods to cities…

Big or small, gardens and green spaces can support and encourage wildlife. If they’re accessible and animals can move between them, there’s always something they can offer wildlife. Trees, compost heaps and log piles are practically all-you-can-eat buffets for hedgehogs and other small mammals, encouraging a feast of invertebrates that recycle nutrients and improve the soil. Rockeries and walls provide sites for insects to sunbathe, nesting sites for solitary bees and wasps, and hibernation sites for frogs and toads. Ponds or water features provide watering-holes and homes for amphibians and aquatic insects. And there’s room for a nest-box in even the smallest garden.

A joined-up habitat

Connecting gardens (and adjacent patches of green such as a grass verge or local park) means that animals can move between different features: making a CD-sized hole in the base of a fence can make a big difference for animals like hedgehogs.

Hedgehog Street (our joint campaign with the British Hedgehog Preservation Society) has more information on hedgehog highways and encouraging hedgehogs in your neighbourhood.

Further info