Stag beetle facts

Status

Nationally Scarce

Population

unknown

Scientific name

Lucanus cervus

Stag beetles are one of the most spectacular insects in the UK. The male’s large jaws look just like the antlers of a stag. They spend most of their life underground as larvae, only emerging for a few weeks in the summer to find a mate and reproduce. Stag beetles and their larvae are quite harmless and are a joy to watch.

As well as reading our stag beetle facts, please help us protect this threatened British species by telling us about where they live near you and by making your garden stag beetle friendly.

Identification

A stag beetle’s head and thorax (middle section) are shiny black and their wing cases are chestnut brown.

Male beetles appear to have huge antlers. They are actually over-sized mandibles, used in courtship displays and to wrestle other male beetles. Adult males vary in size from 35mm – 75mm long and tend to be seen flying at dusk in the summer looking for a mate.

Female beetles are smaller at between 30-50mm long, with smaller mandibles. They are often seen on the ground looking for somewhere to lay their eggs.

The beetle most often mistaken for a female stag beetle is the lesser stag beetle. However, lesser stags are black all over with matt wing cases, while female stag beetles have shiny brown wing cases. Lesser stag beetles tend to have a much squarer overall look.

Download our beetle ID guide for a closer look:

A fully-grown stag beetle larva (grub) can be up to 110mm long. They’re fairly smooth skinned, have orange head and legs and brown jaws. They are nearly always found below ground and can be as deep as half a metre down.

Img: James Wragg

Habitat and distribution

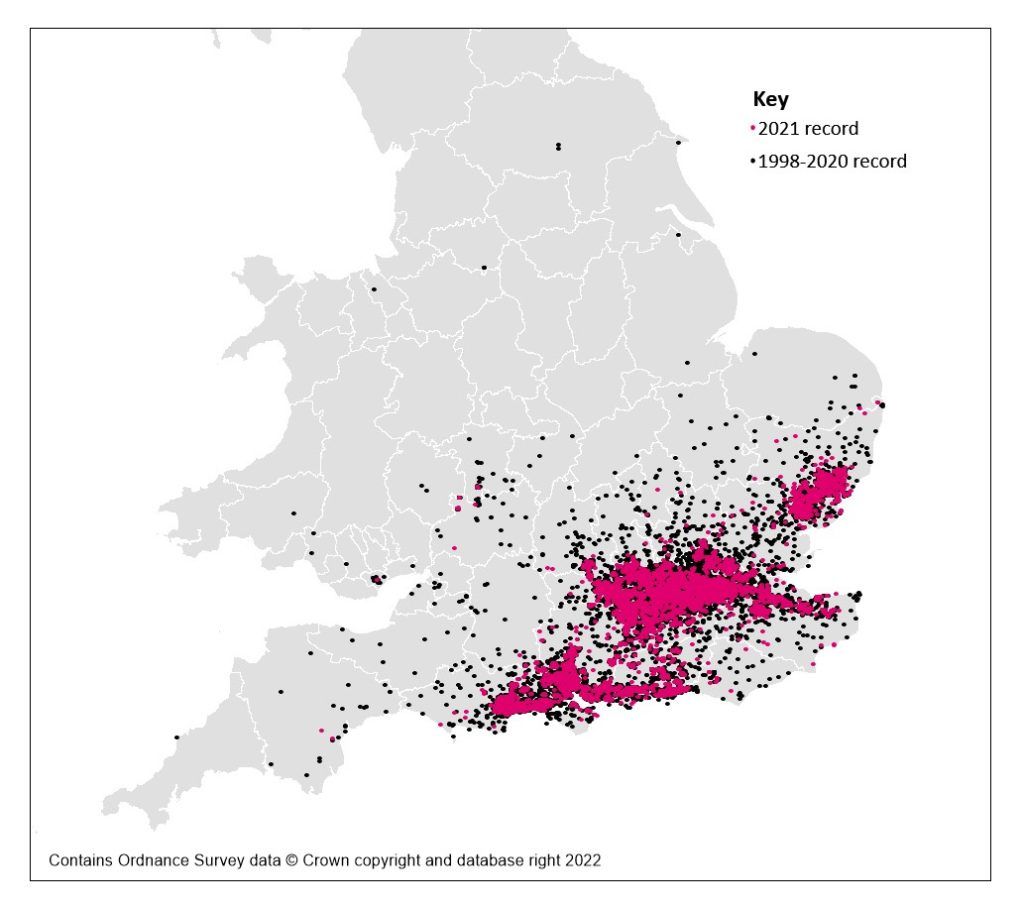

Stag beetles live in woodland edges, hedgerows, traditional orchards, parks and gardens throughout Western Europe including Britain – but not Ireland. Stag beetles are relatively widespread in southern England and live in the Severn valley and coastal areas of the southwest. Elsewhere in Britain they are extremely rare or even extinct.

Female stag beetles prefer light soils which are easier to dig down into and lay their eggs. Newly emerging adults also have to dig their way up through the soil to reach the surface, therefore areas like the North and South Downs, which are chalky, have very few stag beetles. They also prefer areas which have the highest average air temperatures and lowest rainfall throughout the year.

We’re particularly keen for people to record stag beetles in the counties on the border of their known range including Norfolk, Cheshire, Bedfordshire, Somerset, Lincolnshire, Northamptonshire and Shropshire.

Also please keep a special eye open if you’re visiting the following places: Richmond Park, Wimbledon Common, the New Forest and Epping Forest.

Diet

Larvae feed on decaying wood under the ground. Adults can’t feed on solid food – they rely on the fat reserves built up whilst developing as a larva. They can use their feathery tongue to drink from sap runs and fallen soft fruit.

Habits

View photos and description of how stag beetle larvae pupate.

Stag beetles spend most of their very long life cycle underground as a larva. This is at least 3 – 4 years depending on factors such as temperature. Periods of very cold weather can extend the process. Once fully grown, the larvae leave the rotting wood they’ve been feeding on to build a large cocoon in the soil where they pupate and finally metamorphose into an adult. Adults spend the winter underground in the soil and usually emerge from mid-May onwards. By the end of August, most of them will have died. They do not survive the winter. During their short adult lives, male stag beetles spend their days sunning themselves to gather strength for the evening’s activities of flying in search of a mate. This is when you’re most likely to spot them.

View a drawing of the stag beetle life cycle by clicking here.

Breeding

Males are often seen flying around at dusk searching for a mate. They will wrestle or fight other males using their enlarged antler-like jaws. Although they can fly, female beetles are most often seen walking around on the ground. Once they’ve mated, females return to the spot where they emerged, if there is enough rotting wood to feed their young, and dig down into the soil to lay their small, round eggs in rotting wood such as log piles, tree stumps and old fence posts.

Predators

Predators such as cats, foxes, crows, kestrels and others tend to strike at the most vulnerable stage in the beetle’s life cycle, when adults are seeking to mate and lay eggs. Though this is largely natural predation, the rise in the numbers of magpies and carrion crows in the last decade may be having an impact on stag beetle populations.

Threats

The most obvious problem for stag beetles is a significant loss of habitat. Many of London’s surviving open spaces have sadly been developed, including many woodlands. Development will continue to reduce stag beetle habitats, but increased awareness of their existence can help defend the beetles against development.

In addition the tidying of woodlands, parks and gardens has led to the removal of dead or decaying wood habitats which is the stag beetle larvae’s food source. Tree surgery operations such as stump-grinding of felled trees removes a vital habitat for the beetle. Although tidying up still continues in gardens, woodlands and park managers are now much more aware of the need to retain dead and decaying wood as part of the woodland ecosystem.

Humans are, unfortunately, a direct threat to stag beetles. Adult beetles are attracted to the warm surfaces of tarmac and pavements, which makes them particularly vulnerable to being crushed by traffic or feet. Stag beetles have a fearsome appearance and sometimes people kill them because they look ‘dangerous’.

Changes in weather patterns are also likely to have an impact on stag beetles. Exceptionally dry or wet weather is likely to substantially affect the larvae. Wet and windy weather can inhibit adult beetles’ flying ability.

Stag beetles are harmless and do not damage living wood or timber. The larvae only feed on decaying wood so please don’t kill them.

Status and conservation

Stag beetles are legally protected from sale in the UK. They are also classed as a ‘priority species’, listed on Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. If stag beetles or their larvae are known or thought to be present at a site where an application for planning has been submitted, and are likely to be disturbed or destroyed whilst work is carried out at the site, it’s recommended that someone with an understanding of the insects’ requirements be present to see that any larvae or adults are carefully translocated to a suitable natural or purpose-built habitat close by.

These magnificent beetles are Red listed in many European countries and have undergone a decline across Europe. They have gone extinct in Denmark and Latvia, although there has been a successful reintroduction into one site in Denmark in 2013 and a recent one off sighting in Latvia which local experts are investigating further.

We’ve been studying them for nearly 20 years, with the help of the public, and our partner organisations. Our national and international surveys help us to keep an eye on numbers and give the best advice on saving them. We also work hard to protect their homes such as orchards and woodlands.

- State of Britain’s Stag Beetles 2018

- Great Stag Hunt 3 report, 2006-2007

- Great Stag Hunt 2 report, 2002

- Great Stag Hunt report, 1998

How you can help!

Help us protect this unique British species by telling us about where they live near you and by making your garden stag beetle friendly. Download our top tips poster for inspiration:

Dead wood provides food and homes for a multitude of wildlife species. From grand, ancient oak trees, to a fallen apple tree limb in an orchard, to an old buddleia stump in your garden, dead wood is actually teeming with life. You can create your own and add its location to our Log Pile Map to provide us with information about what dead wood habitats are out there and, perhaps even more importantly, to inspire others to do the same.

If you find an adult stag beetle, please leave it where it is, unless it’s in danger of being run over or trodden on. If you have to move a beetle for its own safety, then please move it as short a distance as possible. You can give it some soft fruit or sugar water. If you dig up a stag beetle larva, please put it back exactly where you found it. The next best thing is to re-bury the larva in a safe shady place in your garden with as much of the original rotting wood as possible.

For other stag beetle facts and questions please email stagbeetle@ptes.org.

Research links and articles

Stag beetle mites

Article from the Suffolk Naturalists Society newsletter, by Colin Hawes.

Development of non-invasive monitoring methods for stag beetles

A paper from Insect Conservation and Diversity, by Harvey et al.

A collaborative conservation study across Europe

An article from Insect Conservation and Diversity, by Harvey and Gange.

Bionomics and distribution of the stag beetle across Europe

Article from Insect Conservation and Diversity, by Harvey et al.