Setting up the National Dormouse Monitoring Programme

The National Dormouse Monitoring programme (NDMP) was set up in 1990. It started with only 13 sites but under the guidance and enthusiasm of Pat Morris and Paul Bright it quickly grew and, within two years, there were 28 sites. In September 1992 the first newsletter, called The Dormouse Initiative, was published. Reading it now, it’s incredible how little we knew about dormice 32 years ago. One article correctly reflected how this new monitoring programme would enable us to learn about their average litter sizes and comparative body weights. It also stated we might learn about growth rates in different habitats, which isn’t possible because we don’t mark most of the individual dormice and gathering information on quantitative measures of habitat has proved challenging.

Informing dormice monitors since 1992

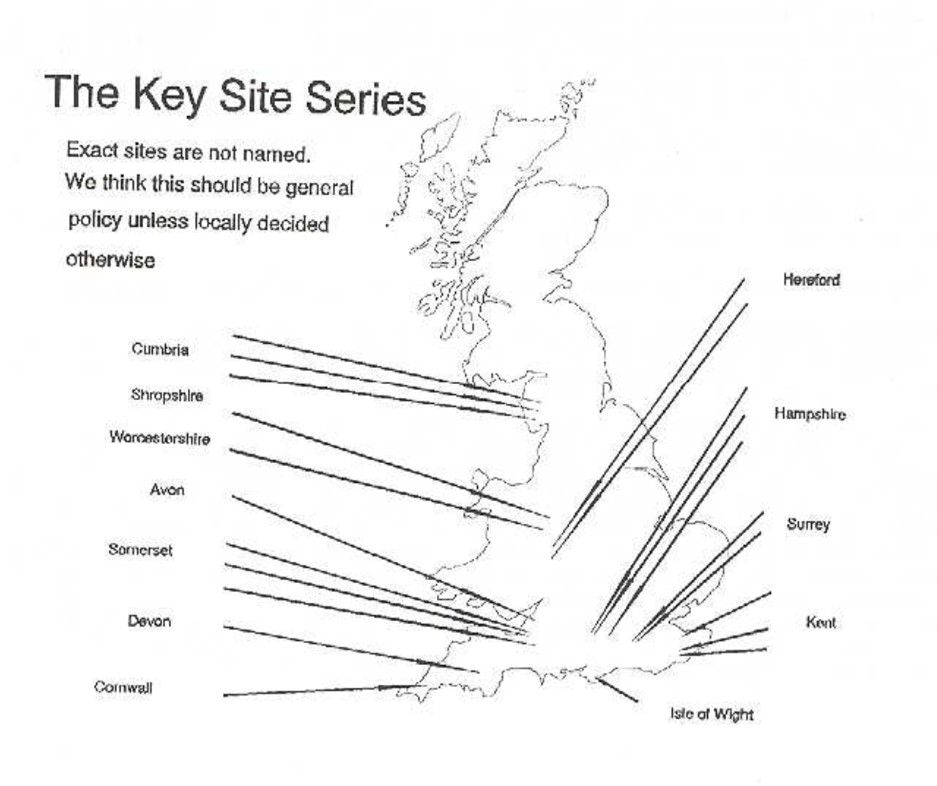

The Dormouse Initiative told dormouse monitors in 1992 that 24 key sites had been set up in 10 counties from Kent to Cornwall and Cumbria. Below is a map of their locations.

The 28 sites that were monitored as part of the NDMP in 1992 are shown in the table below. There were no sites in Shropshire, Cornwall or Worcestershire but sites from these counties were established the following year in. NDMP sites were removed from the programme when monitors were no longer able to visit their sites or when no dormice had been recorded for a substantial period of time. Of the 28 sites that submitted data in 1992, only 12 sites are still part of the programme and home to dormouse populations today. However, the picture is not as bad as it first appears.

The sites in Cumbria – Ulpha and Old Travellers Rest – have developed into canopy woods with no understory and so are unlikely to be suitable for dormice. While the woodland sites in Hampshire are in a similar state, it’s possible that dormice still occupy hedgerows in the wider landscape. We know that dormice are still present at Crab Wood; one was recently rescued by a coppice worker and taken to a wildlife hospital. The state of the woods in Herefordshire is unknown but I’ve been told that Spong Wood in Kent, has also grown into a canopy-dominated woodland and consequently all the understory has been lost. The story is similar at Stawards Wood in Northumberland which is particularly disappointing because it’s a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), designated specifically for its dormouse population. It was also the most northerly native population of dormice at the time; it’s likely they went extinct at Stwards in about 2015. The woodlands in Somerset still have dormice but the numbers being recorded at box checks have dramatically declined. In an effort to help reverse this decline, PTES has recently started work with the local Wildlife Trust and National Trust to investigate where and how sensitive woodland management can be carried out to reinvigorate the habitat and support thriving numbers of dormice again.

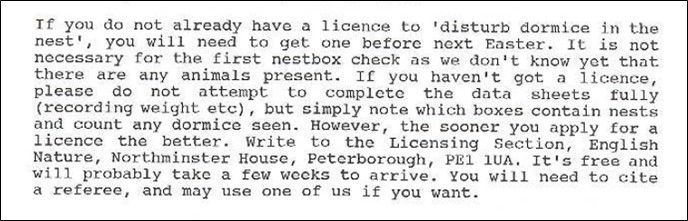

One aim of producing The Dormouse Initiative was to encourage more volunteers to start monitoring NDMP sites, which raised the issue of needing to have a special licence to handle the dormice. In 1992, it seems that obtaining a licence was relatively easy (see instructions below). The applicant was instructed to write to English Nature, cite Pat Morris or Paul Bright as a referee and wait for a couple of weeks. However, as dormouse numbers declined and interest in the species increased, it’s appropriate that the requirements for obtaining a licence have become more robust.

Setting up an NDMP site

Setting up and monitoring an NDMP sites isn’t easy. You need to have access to a site with a known dormouse population, put up at least 50 wooden dormouse nest boxes, obtain a dormouse handling licence (which requires competent management and handling of all life stages) and be able to check the boxes at least twice a year. Today there are about 400 sites which are monitored annually by our dedicated volunteers. Their fantastic efforts continue to contribute to our growing knowledge of how best to look after this charming and enigmatic rodent.

Header image credit Angela Pounder