Below us, as the aeroplane started its descent, the lights of Tashkent stretched as far as the horizon. The capital of Uzbekistan is home to over two and half million people, making it the largest city in Central Asia. I was arriving there, close to midnight, on a visit to meet our Conservation Partner Elena (Lena) Bykova, from the Saiga Conservation Alliance (SCA) who has been researching and protecting saiga antelope in her homeland for 20 years.

PTES has been supporting critical research and conservation efforts to recover saiga populations across their range in Central Asia and Russia for over fifteen years. Saiga antelope, with their long, characteristic noses and large expressive eyes, are immediately identifiable and unique amongst the antelope species. They are much tougher than they look, having roamed the earth since the ice age, outliving species such as mammoths and sabre-toothed tigers. They once migrated across arid plains in eastern Europe, Asia and Alaska, but are now only found in smaller ranges in Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Russia, and Uzbekistan. Saigas are listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List due to declines from over a million in early 1990s to just six per cent of that by 2005. However, thanks to huge, concerted conservation efforts, they are now making a recovery across their range.

In 2016 PTES started working with Lena and the SCA as they investigated reports of a recently re-discovered, isolated population of saigas in western Uzbekistan in the autonomous Republic of Karakalpakstan. This population was small, and miles from the larger populations roaming the steppe elsewhere. Originally living on Vozrozhdeniya Island, in the middle of the Aral Sea, the population had been safe from humans due to the surrounding waters for at least 400 years, up until the beginning of the dramatic, drying period as water was diverted for irrigation. Today the waters have diminished, and the region has changed beyond recognition. Previously flourishing fishery communities are depleted, the area has limited access to water and people are looking for alternative ways to support their families. The island and saiga are now exposed to anyone determined or desperate enough to cross the barren sands, looking for an opportunity to make money. Conservation work is always challenging but in a region like Karakalpakstan, innovative and inclusive solutions are needed. So, Lena’s team began exploratory trips, to a province she’d visited as a child for beachside holidays, to gather more evidence on the saiga and devise measures to protect them, their habitat, and help people living alongside them.

Travelling west along the silk road

Uzbekistan is a pretty vast country and the Republic of Karakalpakstan is the western most region, so we took an internal flight to the regional capital Nukus. It’s a large city near the Turkmenistan border, surrounded by three deserts and home to the world famous Savitsky museum. Savitsky was an artist who devoted his life to gathering a globally important collection of Russian and Central Asian avant-garde paintings banned by Soviet authorities, as well as a large and important ethnographic and archaeological collection from the peoples of the region. I visited the museum at the end of the trip, my tour guide spent two hours explaining the impressive array of art; I could have stayed much longer but the museum was closing.

Our journey was undertaken, in part, to investigate new excursions, stay at guest houses and experience trips in order to put together a tour package that will entice new visitors whilst supporting local communities working in sustainable tourism. We were a large team. Lena and her husband Sasha were accompanied by two entomologists from the Academy of Sciences in Tashkent who wanted to collect beetles. Zebo Isakova, the Project Officer responsible for delivering the annual Saiga Day celebrations, and Nodira Shaabasova, a travel consultant, would lead the work on developing a tour package. They were being helped by local guide Huromet Jalibetov and our driver Bagbergen.

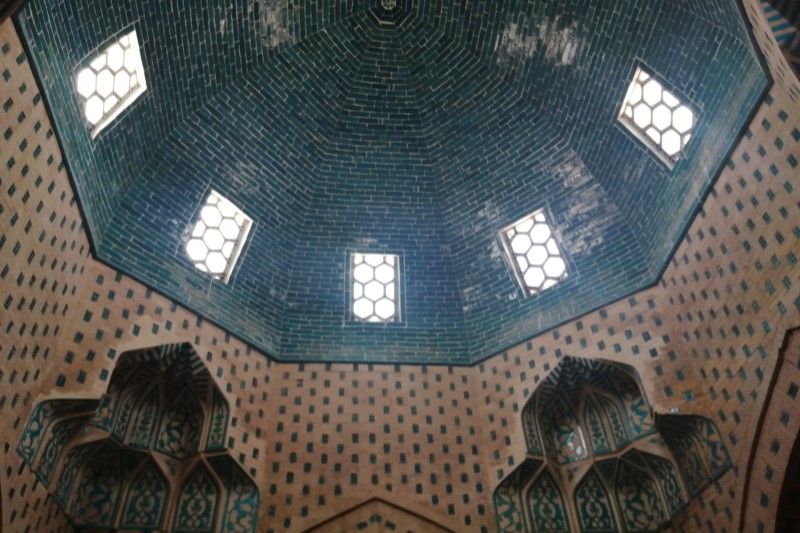

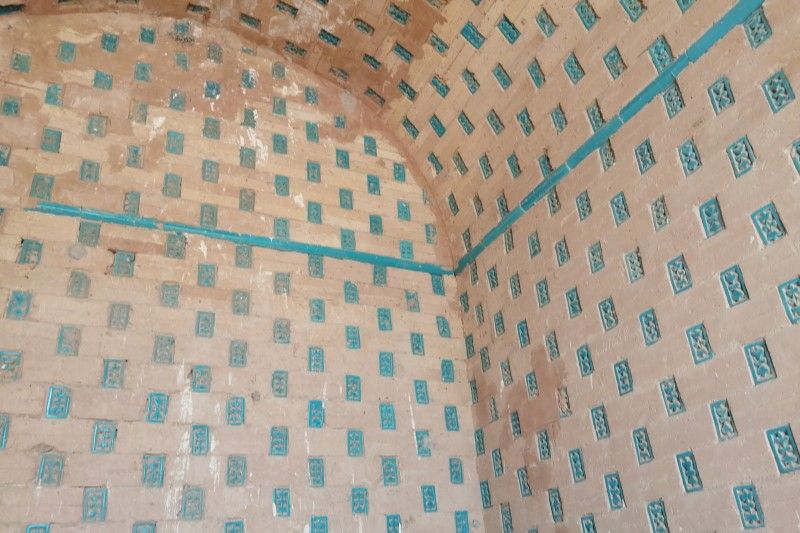

Our next stop, after the Savitsky museum, was the Mizdakh Khan necropolis, a mix of Zoroastrian and Islamic burial sites, with the impressive mausoleum of Maslym Khan Sulu, a key feature of the excursion. The necropolis spans two large hills and is still being used today. We escaped the heat of the desert by descending into the mausoleum which was impressively cool and beautifully constructed, with hundreds of tiny turquoise tiles.

Opposite the necropolis, on a third hill, sits a citadel and fort which is known as Gyaur qala, a term of Arab origin and literally means “Infidel Fort”. There wasn’t much left of the fort but the remains and their prominence in the landscape were an impressive sight.

Crossing the world’s newest desert

Straddling Uzbekistan in the south and Kazakhstan in the north, the Aral Sea was once the fourth largest inland water body in the world. In a land-locked country, bordered on all sides by other land-locked countries, the Aral Sea once offered miles of beach, abundant fishing and supported large communities.

Now the region is a grave warning of our ability to wreak rapid, unchecked environmental destruction. In the 1960s the Soviet Union diverted the Amu Darya and Syr Darya (the South and North rivers) to irrigate cotton plantations. The rivers had previously fed the Aral Sea, sustaining rich ecosystems and thriving economies. The history of Russian interest in cotton production in the region stems from the American civil war when US exports of cotton significantly slowed. Russia looked to Central Asia, where the local peasants’ complex irrigation systems produced increasing amounts of ‘white gold’. Throughout the twentieth century, Soviet interest in increasing cotton production in the region grew but it wasn’t until the seventies that the devastating diversion of water began in earnest.

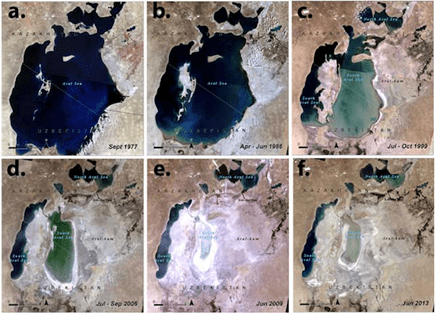

Aralkum now covers most of the area once covered by sea. Literally translated, Aralkum means Aral Sands. The sea has literally been replaced by desert. The world’s newest desert is arguably what the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) called the most staggering disaster of the twentieth century. I’m sure you’ve seen the satellite images of the ever-decreasing sea from the 1970s until the present day. The island I went to visit – Vozrozhdeniya, aka Resurrection Island – is clearly defined in the western region of the Aral Sea in the 1970s. But as each decade passed, the island disappeared, first becoming a peninsular, then just part of the land that lies east of what’s now known as the South Aral Sea. The shoreline of the Aral Sea has changed completely.

In its heyday, the Aral Sea provided 48,000 tons of fish annually – 13% of the USSR’s total fish production. When the water from the two major rivers were diverted for cotton irrigation, not only did the amount of water rapidly drop, but salt particles from the remaining salt flats were blown by the wind, settling on the agricultural fields. It’s estimated that more than 40 million metric tons of salt swept across the land. Now fishing vessels and canning factories lay abandoned and rusting on the desert sands. The South Aral Sea will never recover but people are working hard in the region to ensure that the communities and wildlife that remain are given a chance at a new lease of life.

On the Kazak side of the border, the Kokaral Dam has helped the North Aral Sea begin to recover, both in terms of water levels and fish stocks. South, in Karakalpakstan, the situation is different. The Uzbek government has begun various initiatives. Planting hardy, native species across what was the seabed is happening on an industrial scale. And there’s plans for a new canal to be constructed from the south (Amudarya river delta) to Aral Sea. It would be impossible to reverse what’s happened, but efforts are being directed towards creating new, albeit different, ecosystems and livelihoods whilst trying to prevent further loss and disaster. In some areas the planting is working, shrubs have become established and the tell-tale signs of mammals are evident from the tracks and burrows in the sand. In others it’s failed, the sands are too degraded for the plants to survive. Instead, vast, other-worldly, lunar-like vistas stretch to the horizon, creating a disorientating panorama.

Traversing dramatic landscapes in search of saiga

Rising high above a dramatic landscape of red and white peaks, is the Ustyurt Plateau, on the western edge of the Aral Sea. Underfoot are millions of white seashells, evidence of waters that once teemed with life. In the distance was the new seashore. It’s receding visibly every year. We tracked across the red sands, spotting tortoise tracks running almost vertically down steep slopes, fox scats, and the entrance holes to the burrows of gerbils and jerboas – desert-adapted mammals that cope well in this environment. As we crested another hill, Lena spied the trail of a small group of saiga that had probably passed by a few days before. Great news! In this region the saiga don’t live in vast herds like they do in other regions with more abundant food. Here the animals live and forage in small numbers, moving frequently.

Once we arrived on Resurrection Island, the environment was visibly different; a greater variety of plant and tree species supporting many more creatures, and evidence of their activity was clear. Hare and fox droppings were abundant. Yellow and purple flowers blew in the wind. We soon spotted our first lizard and tortoise. Camera traps had been set up in different locations by Lena’s team some months ago. She and her husband Sasha spent some hours collecting them in and, over dinner, we looked at the footage. It was incredible to see not just the number of different species that make this region their home, but also their behaviour. One camera had been set under a rocky overhang, a secure area that seemed to have been investigated by all the animals in the Island. Hares were abundant; foxes put in an appearance, then swiftly moved on, presumably following the hares’ scent. Caracals and Asian wildcats were caught on camera, as were tortoises, gerbils, black birds, jackdaws and badgers. Not to mention saiga.

During our two-night stay, camping on the island, Lena documented saiga tracks and droppings to add to her map of their activity. The map of sightings will help inform which areas the SCA proposes are designated as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. Getting this status will give additional protection to the region and enable damaging activities such as gas extraction to be limited to outer buffer zones. Since 2016 Lena has been gathering evidence of saiga across the island. The amount of evidence has been declining as gas exploration in the region has increased. One positive outcome of the loss of the Aral Sea for the government has been the discovery of large natural gas reserves. Unfortunately, these are in the area where the saiga also live. So, Lena’s work to demarcate areas for protection under UNESCO status is urgently needed.

Before we left, we drove to a region the team told me was home to ‘dinosaur eggs’; huge geological structures (concretions), lying dotted across the landscape. The geological concretions of what’s known as Renaissance Island arose at the end of the age of the dinosaurs, somewhere in the Upper Cretaceous. The history behind their formation isn’t properly understood but we all agreed that these gigantic features, which echoed the abandoned fishing vessels with their rust-red flakes, would attract tourists and make a great excursion for people interested in unique environments.

Secret Soviet bioweapons lab

Our next destination was the site of the now demolished biological weapons laboratory on Resurrection Island. Throughout the 1940s and 50s, the USSR established a secret military base. Also known as Aralsk-7, the site was developed to create a home for up to 1500 scientists, military personnel and their families, in a newly established town on the island called Kantubek. The laboratories were developed and the scientists began to experiment with anthrax, smallpox, the bubonic plague, and other bacteria and diseases.

The place was never marked on any soviet maps. The site was chosen because it was so remote and completely isolated that it was thought no one would know it existed. In fact, it was kept so secret that, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, it took a whole year before anyone remembered the place existed. A full twelve months after the USSR fell, a team was dispatched to swiftly remove the community, giving them less than a day to grab important documents before they were taken off the island, leaving an eerily abandoned town, with fully furnished homes and functioning laboratories. Now all that remains is scant evidence that people ever lived here. Apparently, a few years ago, a BBC report accused the lab of being complicit in the production of Novichok. Soon afterwards (in 2019) the government ordered the place be razed to the ground; all that is left of the bioweapons labs are large concrete slabs and biohazard warning signs. As we posed for photos in front of the signs, a tiny toad-headed lizard wandered past our feet. Life was beginning to return.

Muynak guest house: a home away from home

Driving back across the seabed, we headed towards Muynak. It had been the regional fisheries capital, back in the heyday of the Aral Sea. Now it lies 150km from the sea’s shore and is home to the notorious ship cemetery. We needed somewhere to stay over the next two days and Nodira had arranged for us to be put up at Veneera’s Guest House in the centre of town. Muyank has limited hotel options and part of this project is assisting local families develop tourist opportunities. Veneera opened her home to us, creating a warm and welcoming atmosphere. We had one room for women to sleep in, another for the men. Dinner was served in a smart dining room next door. Veneera’s family helped her lay the table with multiple appetising dishes, whilst she performed the local tradition of pouring water for us to wash our hands three times before sitting down to eat. Her food was wonderful, and, during the second evening, she invited us into her kitchen to help prepare ‘five fingers’ – a local dish of flat pasta squares, cooked with chicken and vegetables, served in a huge dish scattered with herbs. Nodira and Veneera discussed what aspects of the home stay could be tweaked and we all chipped in with some suggestions but, more commonly, agreed that what Veneera was already providing was a comfortable home away from home.

Silk production and baking

Nodira arranged another opportunity to meet a local family and learn more about local customs and traditions. The region famously sits in the heart of the Silk Road and we had the chance to see some of that silk production close up. We journeyed out of Nukus towards the border with Turkmenistan, the landscape much lusher and more productive than it had been further north. Pulling into a wide square surrounded by low lying farm buildings, we were met by a community leader who ran a silkworm cooperative. He and his neighbours kept silkworms which produce cocoons that they sell to manufacturers who spin and dye the silk. I’d never seen silkworms up close before. We entered long, dark wooden barns, stacks of white mulberry branches lining the walls and the sound of worms munching echoing loudly. It was incredible to see the process: the mulberry grown in narrow banks between the other farm crops, the hungry worms fed twice a day until they’d fattened up sufficiently to spin delicate, pale cocoons, ready for the family to harvest.

We were then invited to help the family cook some traditional food and share a feast with them. Several daughters-in-law took turns preparing bread dough, five-fingers and yoghurt, overseen by the family matriarch who kept a running commentary on the process. I helped make the delicious lepeshka – huge flat discs of flaky bread, mixed with herbs and imprinted with beautiful, stamped decorations. The turkey, pasta and vegetables were cooked in a huge pan over a wood fire under the eaves, then we took our seats in the traditional manner on a raised bed, cross-legged around two low tables filled with food. A fitting end to a fantastic day.

Saiga Day celebrations for the school children of Muynak

Although finding the saiga tracks and seeing images of the animals caught on the camera traps were arguably an exciting part of my trip, the highlight was spending a day with 40 local school children, carefully chosen by their teachers to take part in the annual Saiga Day celebrations. The SCA established Saiga Day 15 years ago. It takes place each May across the saigas’ range. The teams in different countries work with local schools to hold celebrations for children, teachers, and their families to promote the importance and uniqueness of the species, developing a deep pride in the children of their native wildlife.

Our celebration was a huge event, adeptly co-ordinated by SCA, EcoMaktab NGO and co-sponsored by the local gas company UzKorGaz Chemical, which helped by driving the children from the remote Kyrk Kyz and Elabad villages to Muynak and providing gifts for them all. The children competed in art and sports events which had everyone cheering and shouting to a background of loud music. Drama productions in elaborate costumes followed, with each group telling stories of saiga persecution and the need to protect them and their habitats. A key theme that emerged was how closely the lives of the Karakalpak people and saigas are entwined, and how their cultural traditions have enabled them to co-exist peacefully for centuries. Another theme was the importance of water in the region, managing resources and not squandering them. I had the privilege of giving a short talk to open the celebrations and presenting a gift to each child at the end of the day. The teenagers were an impressive group: well-spoken, passionate, confident and – I’m sure – likely to be the future ambassadors the saigas need. The human and wildlife communities of the region have endured real hardships over the past few decades. I hope that this project, with its wide-reaching objectives to extend protection of the land, support communities and build partnerships with strong foundations, gives the people and saiga of Karakalpakstan a brighter future.

Written by Nida Al-Fulaij, Conservation Research Manager at PTES

Header image by Vladimir Sevrinovsky | Shutterstock.com