Overall 2024 was a warm and unsettled year for the UK. It was the fourth warmest year on record in Britain. Eight months had temperatures above their usual average, with February being the second warmest on record, May the warmest, and December the fifth warmest. Winter and spring were both well above average for mean temperatures, with spring the warmest on record and winter the fifth warmest. Despite several periods of exceptional rainfall, overall rainfall was around average. Conditions were much wetter in southern England than average whilst winter was the eighth wettest on record. In February and September, some areas recorded over 200% of the average monthly rainfall. In September, some areas of central southern England had over 300% of the average rainfall, including in Oxfordshire and Bedfordshire. Met. Office Summary 2024

Every year there are reports of dormouse populations doing well at some monitoring sites, where monitors record high dormouse numbers. At other sites, monitors despair over the apparent lack of dormice and wonder whether other sites have shown similar declines. It’s almost impossible to know whether dormouse numbers are stable or not during the year, and so it’s with eager anticipation that we download and investigate the latest dormouse data from the National Dormouse Monitoring Programme (NDMP) database. We take a cursory look at the numbers to see if whether the data hold any surprises, good or bad, and then we send it off to a professional statistician so it can be reliably analysed.

Our statistician – Steve Langton – sent the following report:

The data gathered in May shows some signs of an upturn, but the confidence limits widen at the end of the curve, indicating some uncertainty. Counts of dormice from June and September are roughly level. The significant decline in October between 2023 and 2024 could be an artefact of how the analysis is carried out; we need to wait until this year’s data is reviewed before we can really see what happened between those two years.

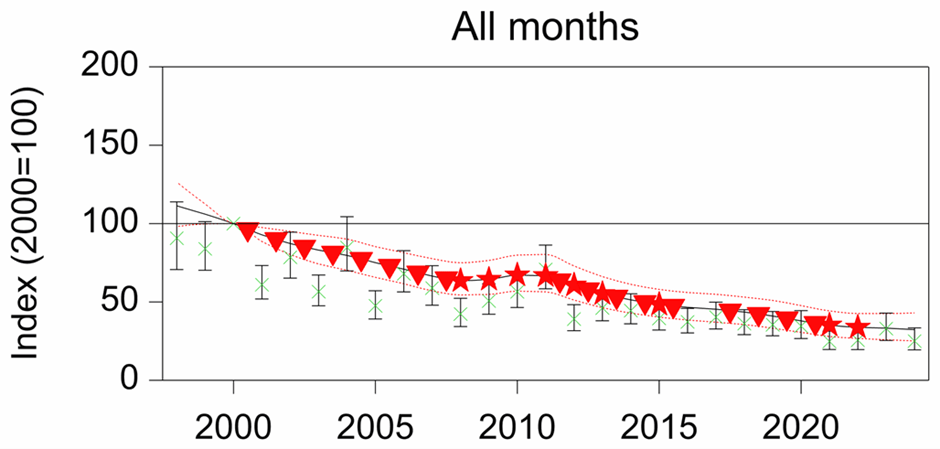

Whilst there are statistically significant differences for different months, they’re sufficiently similar that we can combine all four months into one analysis, shown below. The trend shows a slight, but non-significant decline, from changepoints in 2021 and 2022.

When we combine the data that you gathered during your box checks in May, June, September and October, we are able to produce the chart below, showing the trend in the national dormouse population. The green crosses indicate the estimates of the annual means of the population; the bars are the 95% confidence limits for the annual means whilst red dotted lines are 95% limits for the trendline. Red stars indicate significant (P<0.05) change points, where the slope of the smoothed trend line changes. Red triangles indicate that the upward or downward trend is significant between years.

The message from our statistician is that the dormouse decline is continuing, although the decline in 2024 is ‘slight’.

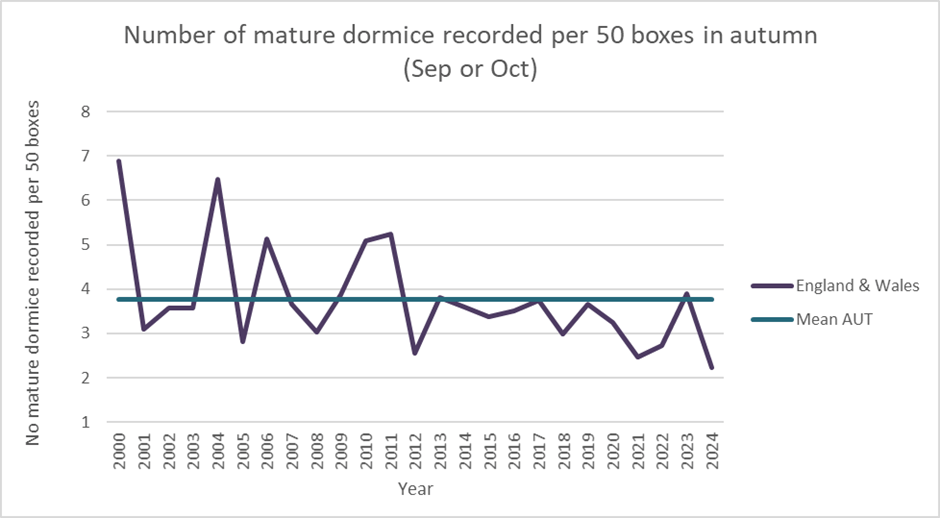

While the analysis we can do at PTES is less robust than that conducted by the statistician, nonetheless we are able to look at comparative data over the years and the areas of specific interest are hibernal survival, early season breeding and numbers of mature dormice recorded in boxes.

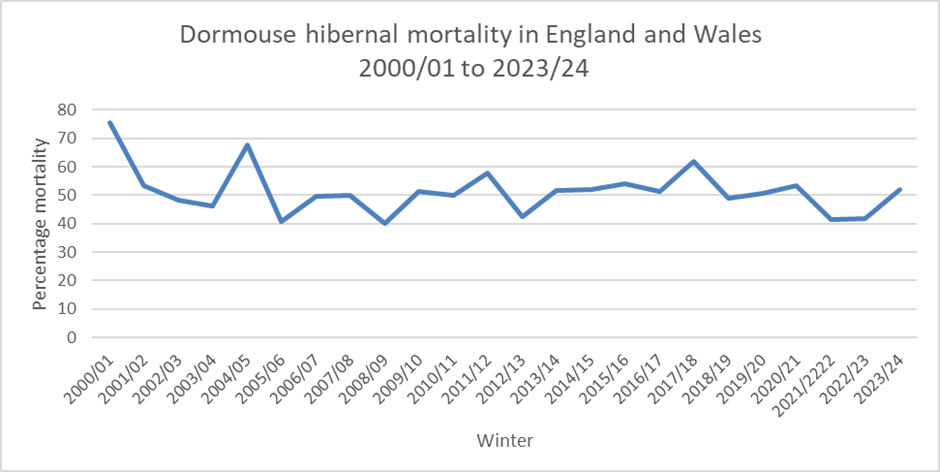

Over winter survival rates

The NDMP was set up to monitor our dormouse population and, in that respect, it’s been very successful. One factor we know could impact our dormouse population is how many animals survive the winter hibernation period. Is it getting worse because of climate change or is the proportion of dormice that die over winter relatively stable? According to the Met. Office, the winter of 2023/24 was the fifth warmest on record and so it might be expected that hibernal survival was worse than the long term average, since warmer weather may have encouraged dormice to come out of hibernation more often that usual. It is possible to get an indication of hibernal survival by comparing the number of mature dormice (juveniles and adults) recorded in the autumn with the number of mature dormice recorded in spring the following year.

These data suggest that 52% of dormice died in the winter of 2023/24, which is very close to the long-term average (2000/01 to 2023/24) of a hibernal mortality of 51%. This suggests that, despite a warmer, milder winter, dormouse overwinter survival wasn’t negatively impacted.

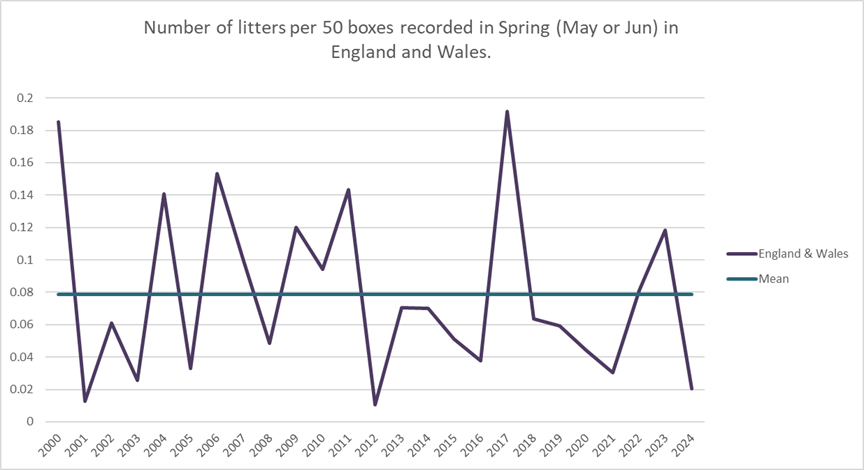

Early season breeding

One concern we have at PTES is the importance of early season breeding to the national population trend and what happens when breeding is delayed. It appears highly likely that some females are able to have two litters a year, especially if their first litter is produced early in the year, in May or June. The young females born in these litters are, potentially, also able to breed and produce litters of their own before they go into hibernation. Our statistician, Steve, concluded:

The data, though far from conclusive, do lend support to the theory that a long breeding season, and particularly an early start to the breeding season, is important if dormice populations are to increase.

In 2000, breeding early in the season was well above average; it then dropped below average for the following three years. From 2003 onwards, a cyclical pattern emerged with the number of early season litters below the long-term average for one year and then above the long-term average for the next. From 2009 to 2011, there were three years when the number of litters recorded in spring were all above the long-term average. In 2012, when we had a very wet spring and summer, breeding throughout the year was severely impacted. Early season breeding in 2012 was the lowest recorded since 1990. There followed a further four years where early season breeding was below the long-term average. After a brief recovery in 2017, early season breeding dropped below the long-term average again between 2018 and 2021 before having a slight recovery in 2022 and 2023. The number of spring litters recorded in 2024 was one of the three lowest recorded in the NDMP over the past 25 years.

It’s possible that a reduction in early season litters may be a result of a changing climate; it’s also possible the low number of early spring litters may be contributing to the ongoing decline in hazel dormouse numbers in the UK.

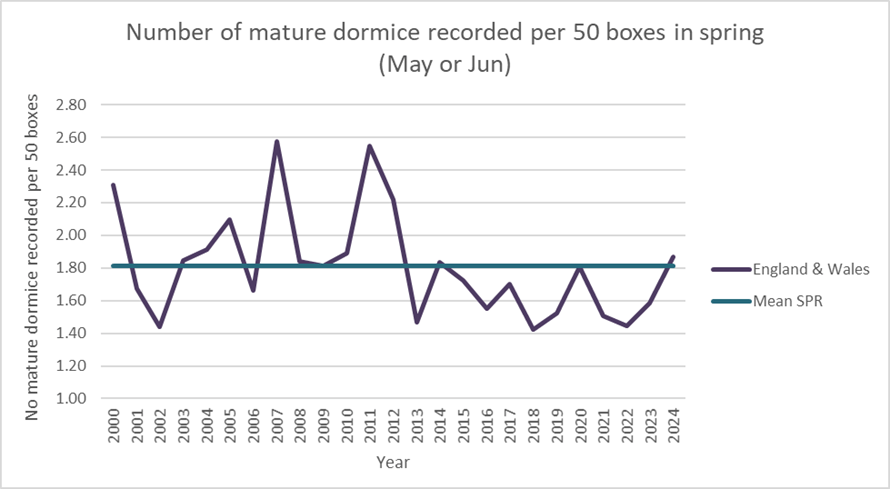

Proportion of mature dormice in the population

Most NDMP volunteers carry out at least two checks each year, one in May or June to gather data on post hibernation numbers, and the second in September or October to obtain a post breeding population. The number of dormice recorded in spring was consistent with Steve’s observation that there were signs of an upturn in May. The number of mature dormice recorded in spring 2024 was slightly above the long-term average. The number of mature dormice per 50 boxes recorded in autumn in England and Wales however, suggests an ongoing decline with the number of dormice recorded in autumn 2024, the lowest since the NDMP started in 1990.

Our data presents a mixed message, which is often the case. Survival during hibernation appears to be within the normal range, however it appears that early season breeding efforts were poor last year. There was a slight increase in the number of dormice recorded in spring, but a downturn in the number recorded in autumn. We do hope that 2025 brings more positive news.

Header image by Jamie Edmonds