Water-pipe bridges provide lifeline for Javan slow lorises and farmers

Shrinking forest homes

Deforestation is one of the greatest threats facing many species today. For many reasons. Every tree that’s lost represents a lost home, lost feeding opportunities and a loss to the local environment. Vast swathes of tropical forests have been cleared in Indonesia. Now hundreds of tree-dwelling species are at risk. Arboreal animals, such as the critically endangered Javan slow loris, are not adapted to life on the ground. Unable to run fast, they’re either restricted to shrinking forest patches or must cross open ground where they’re vulnerable to predation.

Using hosepipes to bridge the gap

Garut District, West Java, home to slow lorises and many small-scale farmers, is characterised by an agro-forestry technique called talun. Talun are ‘home-gardens’, small plots of land on which farmers grow crops, interspersed with shrubs and other native trees. Although not intact forest, these hedgerows, if connected, can be an important habitat for wildlife.

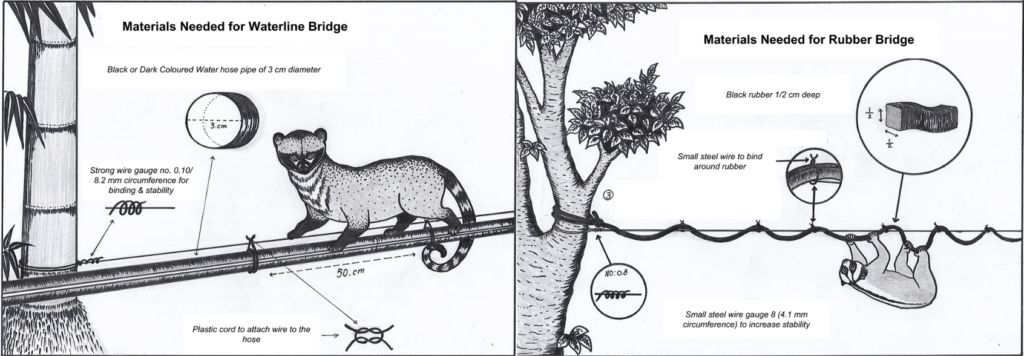

But lack of connectivity was a problem. PTES’ Conservation Partner Anna Nekaris and her Little Fireface Project team are used to solving problems and it wasn’t long before they came up with an innovative solution. Having seen certain species using hosepipe bridges, they decided to experiment. They installed ten different canopy or wildlife bridges in Garut. Five of the bridges were made of waterlines and five from rubber hosing. The team put up cameras to see if the bridges were successful. And they were delighted with the results. Over two years, slow lorises were recorded making over 1,400 crossings on the bridges.

Community support

Cipanganti, the village where Anna and her team worked, sits in a montane rainforest ecoregion, over 1300m above sea level. Working together with local farmers, they discussed the most suitable places to put the bridges up. This including identifying nearby water sources and a slope which enabled the water to flow to the farms. Whilst the cost of the bridge – $30-$40 – may seem cheap to us, for a farmer whose monthly income is about $70, these bridges are pricey. The Little Fireface Project agreed to cover the costs of putting up the bridges if the farmers were happy to pay for the maintenance of the waterlines. The farmers agreed and the scheme was so successful that the Project had to help put up bridges in places outside the study area to ensure equality within the community.

Arboreal bridges popular with many other species

Both types of bridges only worked efficiently when the team discovered that they needed to be wrapped around or tied to wire which ensured their stability. The bridges were put up at an average height of roughly 4.5m, and varied from several to almost 100m long, with camera traps placed at either end. On average the lorises began to use the bridges 10-15 days after they were installed, whilst for civets it took about 36 days. Once they found them, they used them regularly and happily. And they weren’t the only animals that did. Arboreal wildlife bridges are important for creatures that live in the trees but also for birds and bats as places to perch. Anna’s team recorded 17 other species using the bridges including black-striped squirrels and tree shrews, ashy drongos, sunbirds, Javan frogmouths, golden-bellied gerygone and freckle-breasted woodpeckers.

So far Anna and her team are really pleased with the bridges. So are the farmers and it appears the local wildlife is too. And importantly there’s now a direct connection between benefits felt by these farmers and their community, and with the animals that live alongside them.

Thank you for helping us fund this research to protect slow lorises in Java, Indonesia.

If you’d like to support this work, please donate or set up a direct debit here today.

Photo credit A. Walmsley