How an invasive frog might spread Ranavirus to endangered wildlife

When plants and animals are introduced to an area where they don’t naturally occur, they carry a risk of becoming invasive. Invasive species are often highly resilient and competitive, and can be very harmful to their new environment. Just as problematic is their capacity to carry new parasites and pathogens (bacteria and viruses). When this happens, outbreaks can occur, which can have devastating impacts on native species. This is why when a new virus emerges, it’s extremely important that it’s investigated.

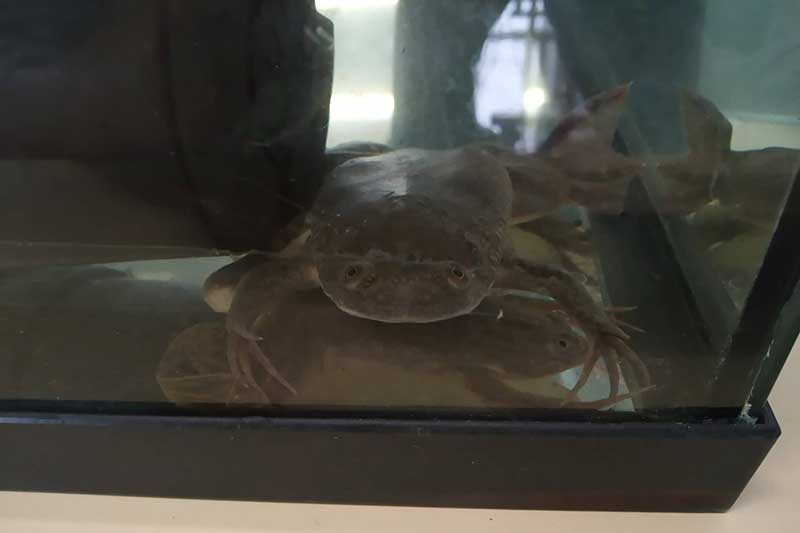

Ranavirus is a new pathogen of particular concern. This is because the virus can infect a wide range of species and is often linked to large-scale deaths of both fish and amphibians in short periods of time. In 2012, Ranavirus was detected in a population of invasive African clawed frog in Oeiras, Portugal. This frog is native to South Africa, and has been introduced to several countries around the globe, including the UK.

Threats to endangered native fish

In Oeiras, the frog shares its freshwater habitat with two native endangered fish species: the Portuguese nase, which is critically endangered, and the Iberian spined-loach, listed as vulnerable. It’s feared that the invasive clawed frog, not only preys on the native fish but is now in direct competition and carrying Ranavirus which could be fatal to these already threatened native fish. Fortunately, in Oeiras, the clawed frog has been the target of a successful project of control and eradication since 2010.

In Oeiras, the frog shares its freshwater habitat with two native endangered fish species: the Portuguese nase, which is critically endangered, and the Iberian spined-loach, listed as vulnerable. Combined with the predation and competition pressures exerted by the invasive frog, Ranavirus could be fatal to these already threatened fish.

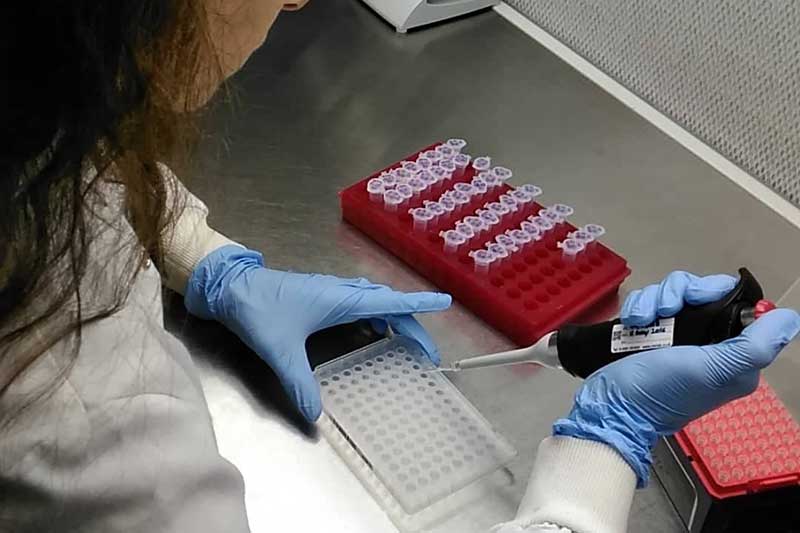

With support from PTES, Catarina Coutinho, supervised by Gonçalo M. Rosa, investigated the Ranavirus dynamics in both invasive and native species in Oeiras. She also explored whether the African clawed frog had a role in the origin of the pathogen in the area. Because the project focused on two endangered fish species, Catarina was able to test new methods of checking for the disease and used two sampling methods with different levels of invasiveness.

What Catarina found out: African clawed frog appears not to be the source of Ranavirus

Catarina and Gonçalo carried out their investigation at the Zoological Society of London (ZSL). Their results revealed that Ranavirus was present in both native fishes with a much higher prevalence than in the frogs. In fact, some of the Iberian spined-loach exhibited clear signs commonly linked to ranavirosis such as, skin haemorrhages.

Despite Catarina’s initial thoughts, the African clawed frog appears not to have been involved in the origin of Ranavirus in Oeiras. However, it doesn’t mean the frog plays no part in the interaction between the disease and native fish. The frogs may still play an important role in the dynamics of the virus. It’s possible the frogs are reservoirs and vectors for the disease. This means that the frogs can help keep the disease stay in the environment for longer and spread more quickly, even if they weren’t responsible for bringing it in the first place. Which means it’s still better to try and get rid of these invasive animals from the wild.

Useful results for the future

At the moment, scientists can only tell if an animal has Ranavirus by testing a piece of tissue (such as a blood sample or a small piece of skin). Unfortunately, that means either finding a dead animal, or putting one down to get a sample. During her work, Catarina trialled taking an oral swab from the fish. Just like in humans, this can be done quickly and painlessly. Encouragingly, the results look promising. It seems that the swabs can find the disease easily. More work is needed but this is really important – especially when we need to focus on endangered species whose numbers are already low.

As the African clawed frog is unlikely to be the source of the virus in Oeiras, our attention has now turned to other exotic species, such as turtles and fish, which were also introduced in the same streams. If exotic species are to blame, it will help to highlight the dangers and the consequences of indiscriminately releasing animals where they don’t belong.

Thank you for helping us fund this research to investigate Ranavirus in endangered fish.

If you’d like to support other areas of our work, please donate or set up a direct debit here today.