Meet Yan Wang: wildlife friendly gardener

In this series, we chat to the dedicated staff members, conservation partners and volunteers at PTES. We find out why each of them chose a career in wildlife conservation, what they find rewarding about their work and what they love most about what they do.

Yan Wang

Wildlife friendly gardening in the Wirral.

How did you get involved with your conservation group?

It took a while, but I am glad I have made a start!

Beginnings

I came to UK in the late 1980’s from China where economic gain was and has been the top priority as a national development strategy. On arriving in the UK I didn’t think there would be an environmental crisis. I saw the greenness of the cities and countryside, birds flying in the sky, established laws to protect the environment and animals, the impressive size of conservation groups, and so on.

Certain events challenged my views, including the articles on disasters in the newspapers and books by the conservation writers including Mark Cocker, Dave Goulson and Thor Hanson. It’s shocking to read that Britain has lost large amount of its natural habitats, with many too fragmented and isolated to maintain a healthy animal population. I was sad to learn that greediness, waste, thoughtlessness and oblivion have been the fundamental instruments for this thorough rapid habitat destruction.

By chance I found myself offloading my sadness and frustration to Sally, a fellow allotmenteer who had already done a lot of work for the environment. I asked, as many politicians are landowners, shouldn’t they do something to make their land more nature friendly to set a good example to the public? She might have found my comment amusing but the conversation we had on that day was probably the starting point to the project.

The Wildlife Garden

In early 2020, several willow trees were cut down for safety reasons on the verge of a disused football pitch owned by local council. At Sally’s request, Hilary Ash, a local Botanist, surveyed the land and subsequently suggested a two-prong project to support the local wildlife:

- “rewilding” the area where the trees were cut with minimum human intervention, and

- planting nectar and pollen rich flowers in an adjacent grass verge to add additional food source for wildlife

Sally was keen on the rewilding practice, inspired by Isabella Tree’s book, Wilding, whilst I was keen on bee-friendly gardening inspired by Dave Goulson. We started the work on our respective patches and soon the project had its name, The Hoylake Willows.

Two years later and with a deeper understanding of wildlife, I named my patch The Wildlife Garden, as part of The Hoylake Willows. There are currently ten flower beds, a log pile, wildlife hotel and a nesting site for mining bees. I’m open to having more features on the site to help the local fauna and flora.

Flower seeds, plants, materials and signs were donated to the Wildlife Garden by people who witnessed the project. Positive and encouraging comments are regularly heard, including, whenever I pass here, it puts a smile on my face.

I am profoundly grateful to Hilary Ash, my fellow allotmenteers and passers-by, who have given their support in many ways and watched the growth and blossoming of the Wildlife Garden with great interest and fondness.

What wildlife have you seen on your site?

Wildflowers

As of June 2022 there are about 60 plant species in the Wildlife Garden, and more new seedlings and wildflower seeds will be planted in the beds later in the season, including bladder campion, common toadflax, red campion, and more black knapweed. The present garden stock is a mixture of wildflowers and (non-invasive) garden cultivars rich in pollen and nectar and with varied flowering times. The majority are planted and some are wild “volunteers” such as white campion, red campion, herb robert, selfheal and field penny-cress. Sunflowers, cosmos, corn cockle, cornflower, yellow rattle, calendula and teasels from last year are self-seeded and it is nice to see them pop out without any input from me! All the nettle-leaved bell flower seedlings planted last year were munched repeatedly to the ground level (possibly by slugs) and I thought I had lost them all. It was a lovely surprise to see their new shoots appearing in the spring this year. It is amazing how nature has its own extraordinary ways.

Invertebrates

At the Wildlife Garden, I have seen bees, flies, butterflies, moths, lady birds, spiders, ground beetles, rove beetles, click beetles, chaffer worms, wire worms, as well as numerous earthworms, woodlice, slugs and snails. I like to watch how far a blackhead earthworm can stretch its body along my palm and wrist before putting it back into the soil. I am sure there are more species out there that I could not identify or have not seen yet!

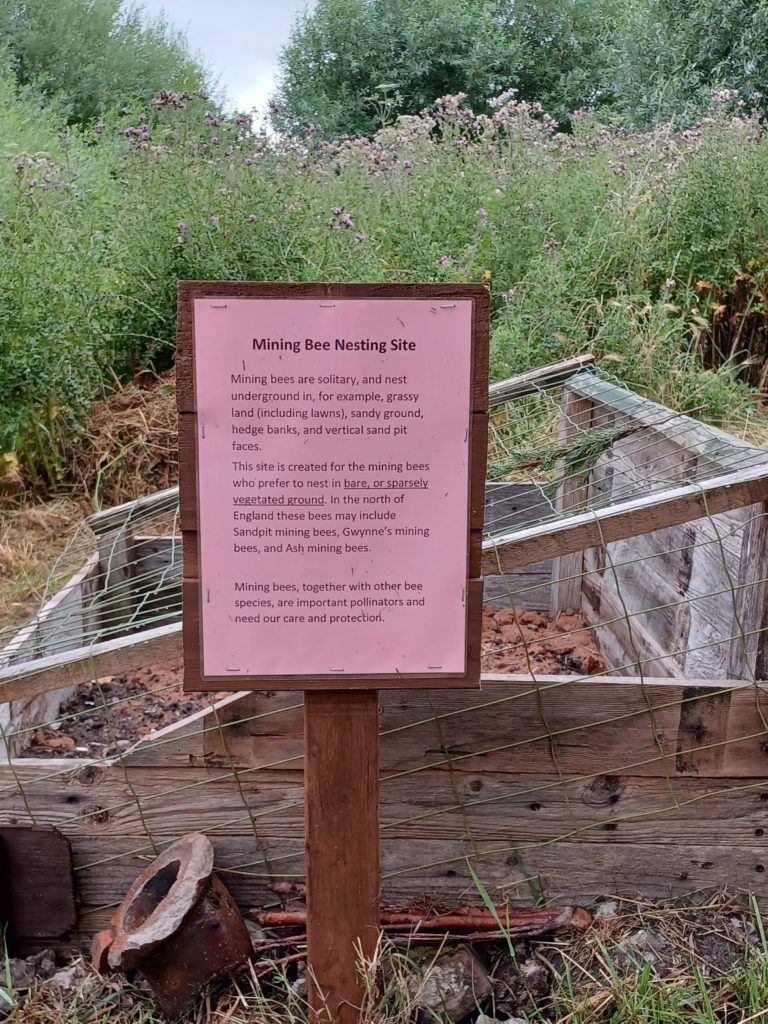

Mining bees

Learning about the wildlife through doing is certainly my own experience. I learned that some mining bees burrow into bare ground or ground with little vegetation to make their nests. Obviously, a bee house above the ground would not be useful for this group of solitary bees, so I built a 1 m² nesting site for them, with a wooden frame to protect the site from the weather and cats and dogs. We shall be patient in our wait for the first bee to use it.

Log piles and stag beetles

I learned that a log pile would be useful for reptiles, amphibians and invertebrates, including stag beetles. The log pile is arranged in a way to create a lot of dark cavities to shelter animals and surrounding the pile is a ring of standing logs buried 50 cm deep into the soil. This is for the stag beetles’ larvae, which live on rotting wood underground for three or five years before transforming into its pupal stage and finally emerging as adults. Although mainly restricted to the southern parts of England, sightings of stag beetles were reported in the nearby Chester area in recent years. We are hopeful!

What’s your favourite habitat/feature and why?

I think all the habitats are unique and important for the ecosystem and biodiversity, and consequently essential to the survival of the human race.

While a lot of environmental news is depressing, we do hear that hedgehogs and bees, though still in decline in general, are now doing better in urban areas. Cities and towns seem to be the last refuge for some wildlife, with gardens, parks and road verges creating great habitats.

Small actions make a big difference

The gardens are within our immediate power remit and have a lot to offer to wildlife. We could try to get rid of or reduce the concrete and plastic coverings from gardens, plant wildflowers, stop using pesticides, make hedgehog and bee houses, build compost heaps and log piles and stop being lawn fanatics. In my case, it is hugely rewarding to see bees buzzing around, and most excitingly hedgehogs in the garden!

Like many people, I don’t have the capacity to be a policy advocate to generate wider impact on habitat restoration. However, I can still influence the policy process by signing petitions initiated by specialist individuals and groups intending to protect the environment and biodiversity. I also support conservation charities to restore and maintain habitats by donation and subscribing to their membership. Taking part in monitoring schemes, such as the UK Pollinator Monitoring Scheme, helps to build up the evidence base on which relevant policies can be made, as well as being a good way to learn about animals and plants.

Every little effort adds up.

What maintenance tasks do you carry out on site? Does this change seasonally?

In springtime, the disused football pitch is carpeted in yellow from dandelions, buttercups and red-tinged grass seed heads. The pitch verges where the Wildlife Garden sits, however, is another picture, where tough grasses, ground elder, docks, nettles, goose grass, and great bind weeds dominate.

Digging for victory

To introduce new plant species and effectively achieve flower diversity, I had to remove the thick root matt formed over the past 30 years. I don’t have access to any machines and am dead against using any chemicals so I use a trusty sharp digging spade. I had a lot of time at my disposal during lockdown and the sandy soil in dry weather spells made digging a lot easier.

Digging can be destructive. I feel terribly sorry for the earthworms and chrysalis dug up from their hibernation or development. I do wish they could survive the disturbance. To reduce the casualties as much as possible while tackling the strong root mat, I tried different “no digging” methods, including planting yellow rattle (a parasitic plant) to reduce the strength of the tough grasses, covering the ground with a weed suppressing sheet for several months before planting, and using ground-cover plants such as creeping comfrey.

Up to now, approx. 40 m² ground is cleared of root mat and made into eight irregularly shaped flower beds, plus two experimental no digging beds with yellow rattle and creeping comfrey. At the moment the beds are bubbling with colour and growing energy.

Sowing seedlings

The season starts in the springtime with geminating the seeds indoor in seed trays – an economical and ecological way to produce seedlings. Almost all plants in the Wildlife Garden were raised from seeds, except 21 yellow rattle plugs bought in 2021. Now I have learned that the seeds, particularly some wildflower seeds, will do better if sown directly into the soil during the previous autumn – for much stronger and healthier growth when the weather gets warmer.

As the soil has rich seed deposits over the decades, weeding is necessary before the intended seedlings establish themselves. Only those found plentiful in other parts of the verges are removed, such as the docks, hogweed, nettles, ground elder, goose grass and bindweed. I would keep unknown volunteer plants to find out what they are. This year, with the help from Hilary, I learned what a field pennycress looks like!

Other tasks involve watering the seedlings in long dry spells and strimming the paths regularly to make it safe and pleasant to walk on.

When the autumn comes, seeds are collected, and then the cycle starts once again.

Do you have a love for a particular species and if so, why?

I love all the animals, big or small, “charismatic” or “dull”, “beautiful” or “ugly”. However, in the past couple of years, I have developed a soft spot for invertebrates, which constitute 97% of Earth’s animal species known to humans.

It all started with an online course “Discovering Earthworms” run by the Field Study Council (FSC), which I accidently came across last year. I was fascinated by this humble creature and how important it is at the base of the ecosystem.

After that I moved on to other topics including bees and bumblebees, beetles, ants, reptiles and amphibians, spiders, slugs and woodlice through online courses and YouTube. I am currently on an online course “Field Identification of Spiders” run by FSC. I don’t think I will ever be able to remember all the details and their scientific names, but the basic understanding such as what habitat they require, what ecological roles they play, and how they might be harmed is sufficient to do the right thing to help them. Without these often invisible and forgotten creatures, nothing could be sustained.

What’s one thing everyone can do to help wildlife in their garden or local green space?

The speed of insect decline is accelerating. The number of flying insects in this country has plummeted by almost 60% since 2004. What will the world be like if we carry on with our selfish and destructive activities? By taking into account our own resources and availability, we can start to help. After all, we are part of nature. If nature goes, then so do we.

Learning about wildlife can be overwhelming. My experience is to start with one type of habitat or insect (or any other animal or plant) and its relationship with humans: what it is, what it does, how it became what it is now, what impact human activities have had on it, and what we can do to help.

Fortunately, there are a lot of materials in the public domain nowadays that can be easily accessed via social media, internet, and printed materials. A lot of conservation charity organisations are doing an excellent job in promoting citizen science. The power of public involvement can never be underestimated in tackling the environment crisis and that includes both you and me.

If you’d like to give nature a helping hand by carrying out a few simple tasks in your garden, have a look at our top tips and guides to wildlife friendly gardening: