Using dormouse records sent in to the National Dormouse Monitoring Programme, we’ve been creating a map showing suitable habitat for hazel dormice projected across England. We can then use this map to help work out the best places to release dormice or to identify areas where dormice are most likely to be found.

Developing a model to analyse dormouse habitat suitability

A team of researchers and conservationists, based at the University of Liverpool, PTES and the Cheshire Wildlife Trust, has been investigating how to use computer models to analyse dormouse habitat suitability across England. Recently published in the journal Conservation Science and Practice, this article summarises the research in “Applying remotely sensed habitat descriptors to assist reintroduction programmes: a case study in the hazel dormouse”.

Developing a way to measure habitat suitability for dormice could help our reintroduction programme by identifying potentially suitable sites remotely. It also means that we would be able to locate areas which are most likely to contain remnant populations of dormice, to identify areas we should prioritise for dormouse surveys (for example during mitigation and development).

To do this, we gathered remotely sensed open access maps from various websites. There were 51 maps in total, which each contained information on a certain type of habitat. For example, there was a map which showed broadleaved woodland across England and a map which showed the distance to roads. Using dormouse records from the NDMP, we could identify the most important habitat factors associated with natural populations and then use this information to calculate what we called “habitat suitability scores”.

What the results show

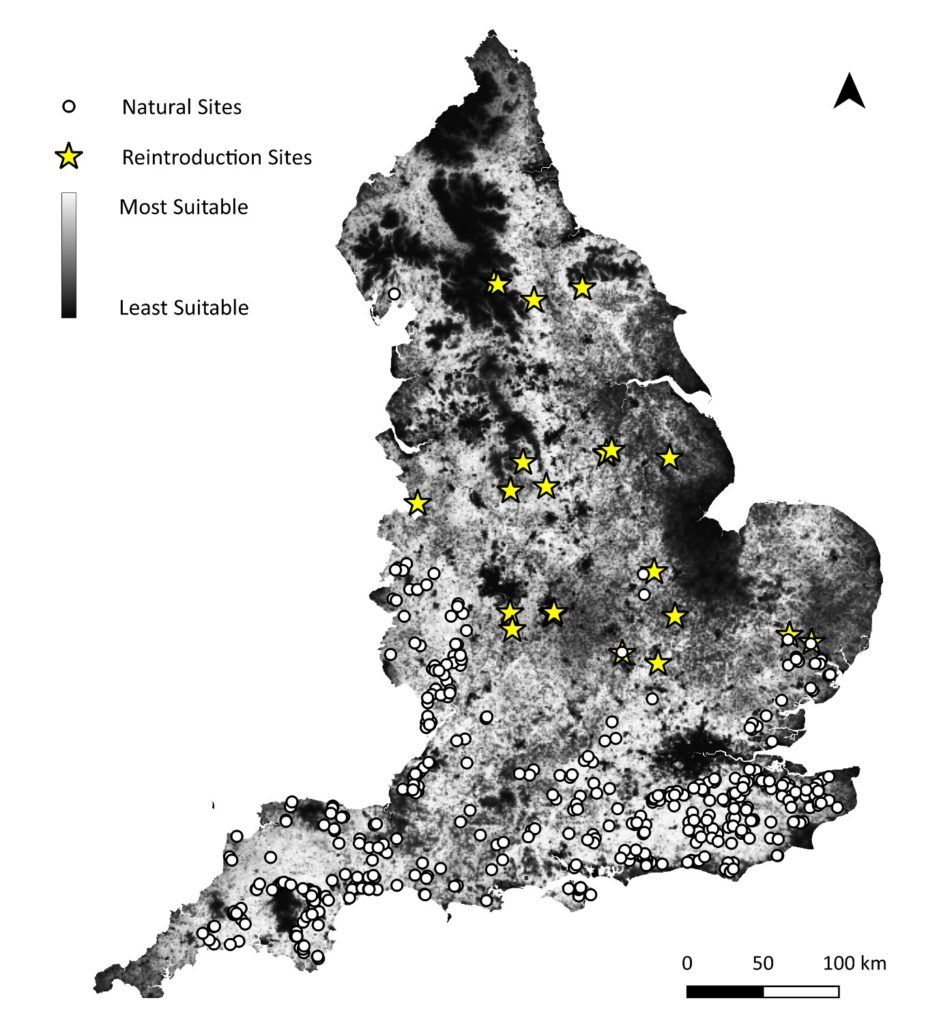

We projected these dormouse habitat suitability scores on to a map of England. The results are really interesting. It shows that suitable habitat in the north of England is much more disjointed and infrequent when compared with that in the south. This could help to explain the relatively recent (last 100 years) contraction of dormouse distribution, which is now largely restricted to the south of England and parts of Wales. Secondly, it shows that there are still some substantial areas of suitable habitat, which may be appropriate for future reintroductions.

The habitat suitability model suggests that dormice prefer a relatively high amount of broadleaved woodland in the surrounding landscape, steeper than average slope gradient, fewer urban areas and less arable land in the immediate landscape and higher levels of coppicing. This is really useful because it confirms much of what is already known about dormouse habitat choices, but also gives some further quantitative insights.

What are the key habitat preferences?

As part of our research, we also studied the effects of these key habitat preferences on population numbers at existing reintroduction sites. The most important habitat factors that influence natural populations also had an impact on the number of adult dormice found in nest boxes at reintroduction sites. These factors are: the extent of broadleaved woodland nearby, the gradient of slope at the site and the amount of arable land in the surrounding area. We found that dormouse numbers are higher in more easterly sites, which is interesting, and may reflect the changing weather conditions across the longitudes of England. The results also show that significantly more dormice are found in autumn, as you will know if you go out monitoring! Sadly, as is the case across the rest of the country, we found that dormouse numbers are also declining at reintroduction sites.

Suitable habitat is vital for reintroduction sites

Interestingly, neither the number of dormice reintroduced nor the number of reintroductions that have taken place at a site had any impact on the current population size. There was also no correlation between the size of the woodland at each reintroduction site and the number of dormice recorded in nest boxes. This doesn’t mean that there is absolutely no effect, but that the other variables are much more important at the 24 reintroduction sites we tested. Therefore, it does show how vital suitable habitat is for reintroduction sites both in the actual woodland and the immediate vicinity, further supporting the use of a habitat suitability model and maintaining suitable habitat at a site.

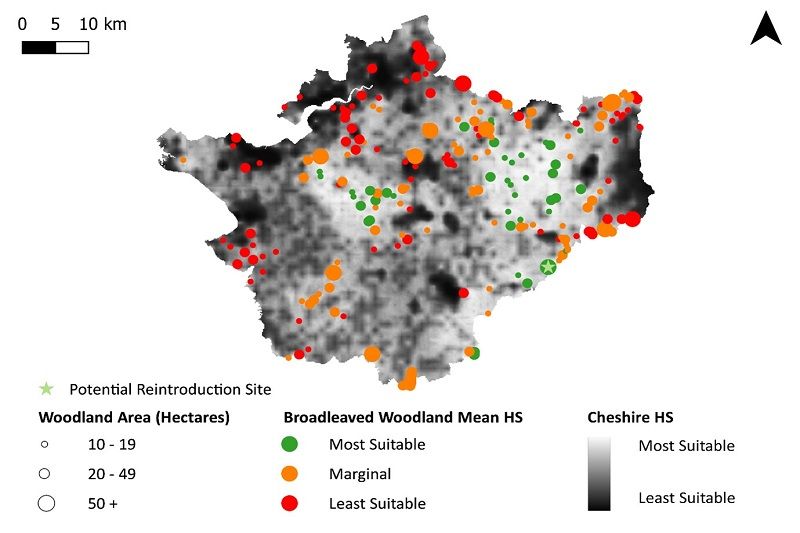

Reintroductions in Cheshire

We used all this information to take a closer look at potential areas for reintroduction in Cheshire. The third dormouse reintroduction took place in south Cheshire in 1996. Unfortunately, the woodland has matured and there are no longer any signs of dormice using the nest boxes. I also carried out a footprint tunnel study in 2019, but found no evidence of dormice using this method either. (Interestingly, there were a few dormouse-nibbled hazelnuts found at the site in 2020, but that is another story!). This lack of dormouse evidence in Cheshire ties in nicely with our modelling results, with the 1996 reintroduction site now being classified as ‘least suitable’. The model described 45 woodlands as suitable, which you can see on the map in green. There are a few areas that contain clusters of suitable habitat (such as in central Cheshire), which we would recommend for future reintroductions, with the idea of creating well-connected metapopulations.

Overall, this habitat suitability method provides a useful tool to help identify potential sites for future reintroductions and to find priority areas for survey during mitigation and development. The same method could also easily be translated into suitability maps for other species, thus offering the possibility of assisting other reintroduction programmes.

Cartledge, E. L., Baker, M., White, I., Powell, A., Gregory, B., Varley, M., Hurst, J. L., & Stockley, P. (2021). Applying remotely sensed habitat descriptors to assist reintroduction programs: A case study in the hazel dormouse. Conservation Science and Practice, e544.https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2 .544

Written by Emma Cartledge.