Lions will only survive if conservationists make bold, brave decisions and devise innovative strategies – and that’s what PTES Conservation Partner Amy Dickman is doing across swathes of East Africa where lions are found.

Dangers to lions and humans

Imagine, says Amy Dickman, joint chief executive of the conservation group Lion Landscapes, that you were an alien and came down to Earth for the day. What do you think you would make of cars? ’You’d see all these metal creatures storming around and killing and injuring god knows how many people a year,’ she points out. ’And yet, we still have them around and, not only that, we pay for them, too.’ ‘But, of course,’ she goes on, ‘cars – on the whole – make our lives better, so it’s a choice we are happy to make.’

Many people living in rural parts of countries such as Kenya, Tanzania and Zambia also live with dangerous entities that can kill and maim, but – on the whole – they’re not cars, they’re cats. Big cats. Predators such as lions and leopards, and also other carnivores like wild dogs and hyenas, and even some herbivores such as elephants and hippos. And unlike our relationship with cars, these people don’t get many, if any, benefits from the wildlife they’re forced to live alongside. In fact – unless they live in an area popular with western tourists – the wildlife is largely a drain on their pockets. Lions and leopards take their cattle, goats and sheep and, in some areas, they’re excluded from traditional grazing grounds to protect these same wild species. No wonder they occasionally resort to illegally killing them with poisoned carcasses or snares. These can be horribly cruel deaths, but livestock are many communities’ most valuable possessions. Of course they’re going to do anything they can to protect them. As Amy says, ‘We are expecting people to carry on living with lions as a species for a pittance, and I’m amazed this has persisted for even this long. The model is broken, and we need to do better.’

Creating space for lions

But just how broken is the model? How are lions are faring? Latest research suggests there are around 24,000 wild lions in Africa today, a stark decrease in abundance relative to the estimated 200,000 about 100 years ago. Other studies show that lion numbers declined by 43 per cent in the two decades between 1995 and 2015, though they went up in some southern African countries. The really big losses took place in West, Central and East Africa. As a comparison, the latest tiger population is put at around 4,000 individuals, while leopards number something like 700,000 in Africa alone.

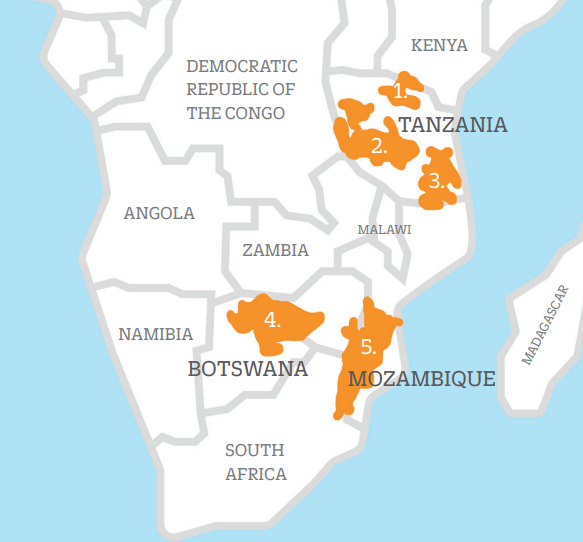

The map shows the five most important lion populations in Africa. There are also good numbers in Namibia and southern Botswana, and a small relict population of Gir lions in India, a reminder the species was once found over much of Africa, Asia and even Europe.

- Serengeti and Masai Mara region of Tanzania and Kenya.

- Greater Ruaha landscape of central Tanzania.

- The Selous.

- Northern Botswana/Southern Zimbabwe.

- North-east South Africa and southern Mozambique.

So, lions are definitely in trouble, but they are not – Amy stresses – about to go extinct any time soon. They need help, but there are plenty of reasons to be optimistic that they can survive into the foreseeable future as long as we do the right thing. But what is the right thing? How do we make space for lions? ‘We need to make dangerous wildlife a net value to people, and then for those people to choose to have them and feel they have a genuine choice,’ Amy says.

Camera traps for conservation

Over more than the past decade, Amy – recently made the director of University of Oxford’s prestigious Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) – has been working in Ruaha National Park in central Tanzania, working out why lions are declining and then trying to come up with solutions to these problems. The solution she arrived at was to deploy remote cameras in villages across the park. Visiting wildlife is recorded, earning those villages points depending on the species, with predators gaining more points than herbivores. Every three months, the points are totalled, and the group of villages with the most gets a $2,000 cash prize. The point is to directly link the presence of wildlife with benefits for the local community – of course, species such as lions, leopards and hyenas also bring problems, as they don’t only predate livestock, they can also be a direct threat to the people themselves. This results in conflict and – quite regularly – illegal killing of these animals. Amy’s abiding principle is that the benefits of having them must outweigh any difficulties they cause.

Creative solutions to the world’s biggest problems

And now with her new initiative, Lion Landscapes, Amy, together with colleague Alayne Cotterill who runs a similar lion conservation programme in Kenya, is taking this idea of wildlife adding value to people’s lives one step further. The Lion Carbon project is perhaps the most innovative of these, a programme that raises international finance for communities in Zambia based on the intact ecosystems that sequester or store carbon, thus offsetting those released by the burning of fossil fuels and helping to reduce the impacts of climate change.

According to Lion Landscapes, this programme is now directly benefiting more than 35,000 households in Lusaka and Eastern Provinces in Zambia, areas which include the wildlife-rich Lower Zambezi and South Luangwa Valley National Parks, both important large ecosystems for lions and other carnivores. More than $4.3 million has been paid out, with funding also going to train and pay 105 community scouts to enhance wildlife protection in partnership with state-funded parks and wildlife rangers. Amy says the idea is to use lions as a barometer for the health of the ecosystem. ‘The fact that you’ve got habitat, the fact that you’ve got prey and the fact that you’ve got tolerance for these species – all these things are represented in the presence of top carnivores. And landscapes with a higher density of top carnivores are worth more than those that are below their carrying capacity,’ she says.

Another innovation Lion Landscapes is working on is Lion Friendly Beef, a variation on the concept of, for example, rainforest friendly coffee, whereby consumers are guaranteed that the product they are buying won’t have had adverse environmental impacts (and they usually pay a premium for it). Both these ideas could eventually be working across much broader areas of Africa where lions are found. That’s crucial if lions and other charismatic species are to have a real future because they provide ongoing, sustainable funding for their conservation.

Wildlife value

At present, conservationists are mostly fire fighting in their efforts to protect wildlife while – as Amy puts it – there are huge conflagrations breaking out all around them. She accepts that many people will find these market-based solutions to wildlife conservation problems difficult to stomach because they worry they give the impression that nature’s only importance is in its commercial value. ‘My argument is I would love to see a different world where we don’t value Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and dollars over everything else,’ Amy says. ‘I would love that. But it is the current system, and we have so little time to turn the tide of biodiversity loss. And it’s not as if we are saying wildlife is only worth what its credit value is, it still retains all its other value, its ecological value.’

Lion Landscapes is also continuing to advocate more standard mechanisms for protecting lions – helping livestock herders acquire lion-proof bomas, for example, is another way to reduce conflict, while the Lion Defenders programme – in which local people are trained as wildlife rangers – has been hugely successful. The challenges facing conservationists to protect wildlife both in Africa and the rest of the world should not be underestimated, but the work and vision of scientists like Amy Dickman and her many colleagues shows what’s possible. If we can take account of how people live – and even more importantly – want to live, then lions and all the many and varied species in the food chain beneath them will survive and thrive well into the future.

Thank you for helping us fund this research to protect carnivores in Tanzania.

If you’d like to support this work, please donate or set up a direct debit here today.

Find out more about our work to protect carnivores in Tanzania: