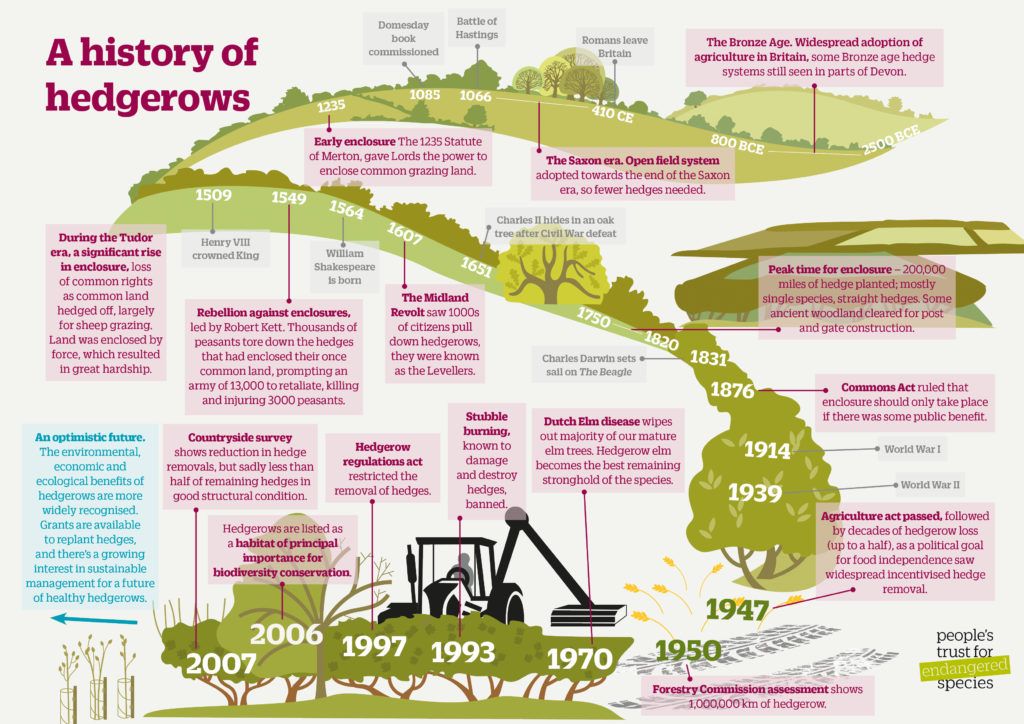

A history of hedgerows

The history of hedgerows reflects huge political change, agricultural development, invasions and riots. The hedges that criss-cross our landscape sometimes have a checkered past, their history is entwined with ours.

The UK’s hedgerows are iconic; important to us both culturally and historically. It is difficult to picture our countryside without the network of hedgerows, with which we are so familiar. Delving into the history of hedgerows unearths many interesting questions. Have they always been a part of our farming systems? When in history did we start using hedges, and how has that changed? One thing is for sure, many are considerably older than they appear.

A future as rich as their history

We don’t know exactly when hedges were first planted, but there is evidence that there has been some form of field boundary since the Bronze Age. Some of these still remain as the banks below some of our most ancient hedges. The lines of feudal boundaries can be traced from our old hedgerows, reflecting social and political changes across the centuries. Old hedgerows also serve as a floral fingerprint of the lands from which they were derived and have collated the signatures of agricultural change over time.

While we may think of the period of enclosure when we think of hedge planting, about half our hedges may well be older than this, some potentially hundreds or even thousands of years old. These ancient hedgerows are hugely valuable thanks to their continuity, undisturbed soils, diversity and seedbanks.

Although it is not always easy to tell the age of a hedge, there can be clues in the shrub mix, in the trees and in the plants that are found at the base. Ancient hedgerows are irreplaceable, both in terms of the wildlife habitats that they provide, and in terms of what they can tell us about the history of our countryside. They undoubtedly still hold secrets about our social and agricultural heritage that is waiting to be discovered.

For all of these reasons, they should be maintained, protected and cherished for their inherent value. We should not only aim for the survival of hedgerows but also for their health. Healthy hedgerows have greater wildlife value and a more secure future. Perhaps we can all aim to be hedgerow champions and help to make sure that their future is as rich as their history.

Hedgerows through the years

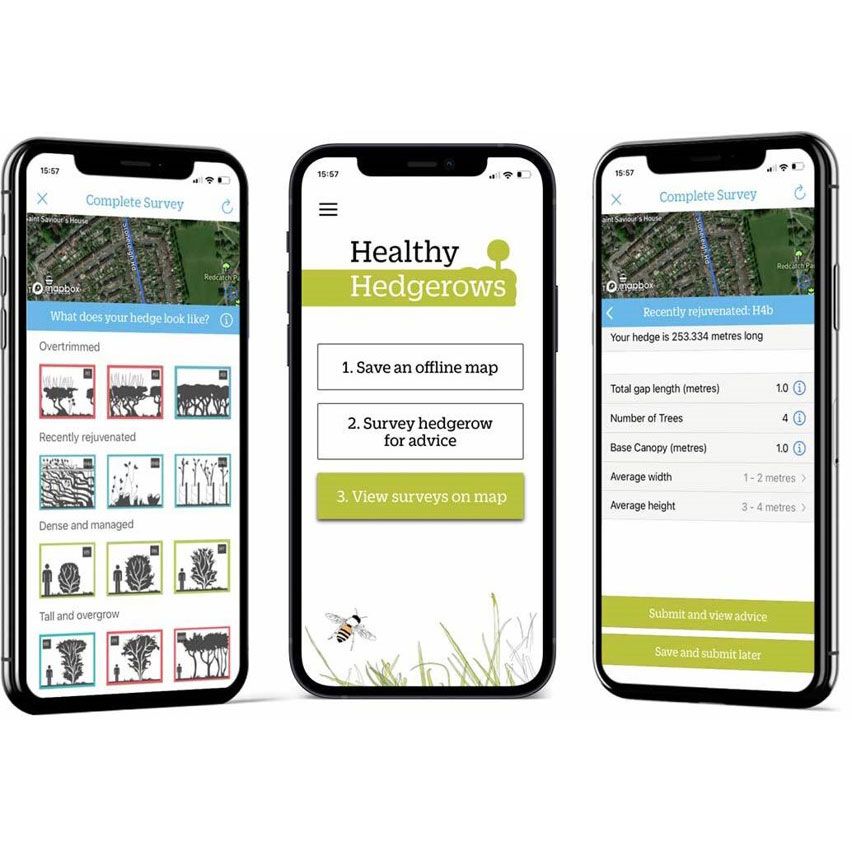

Health-check your hedgerows

The Healthy Hedgerows survey provides instant feedback about the health of the hedge and bespoke management advice. The data that you contribute helps us to understand the overall health of hedgerows at a national scale so that we are able to direct our conservation work. Learn more: