Learning to live with Asiatic wild dogs

Recolonisation can only be successful if the threats which drove the species to extinction previously, are either completely eliminated or significantly reduced

Funding for this project has now finished

Wild dogs get bad press

Asiatic wild dogs are a little-known species that, despite living over quite a large area of Asia, may number as few as 1,000 individuals and no more than 2,300. Large carnivores are having a hard time all around the world. As top predators they consistently come into conflict with people. This is particularly the case with livestock herders whose very livelihood is under threat when their animals are not given sufficient protection.

Wild dogs get a bad press in Nepal, almost as bad as hyenas. The fact that the Nepali word for the wild dog (bwanso) is also used to refer to the wolf is part of the problem. Bwanso is also used as a description for a ruthless or evil human being. The Gurung people in the Sikles region of the Annapurna Conservation Area compare the bwanso to an untamed wind — it can be anywhere at any time, but is difficult to control. Elders who used to see wild dogs in abundance today report very few sightings. Their numbers have drastically decreased over recent years, due to loss of prey and persecution in the mid-hills of Nepal.

Eliminating the threats

However, recent research in Annapurna Conservation Area revealed that the species is trying to recolonize the area. This is great news but the wild dogs will need a helping hand. PTES is providing funds for Yadav Ghimirey and his team at Friends of Nature to offer that help.

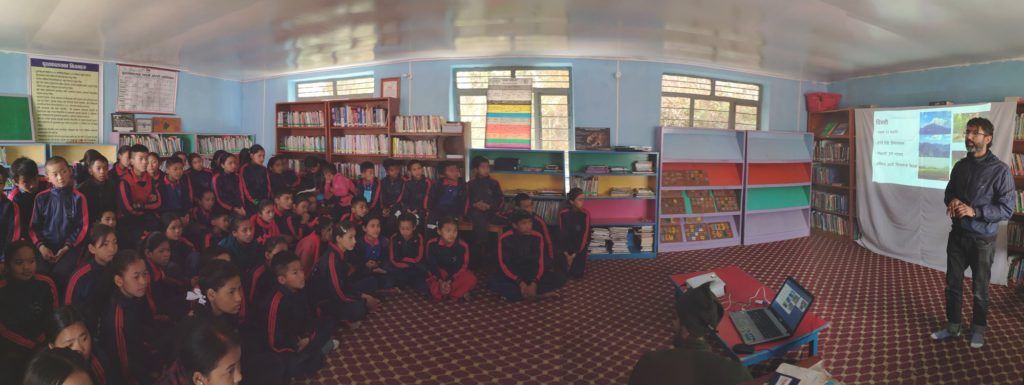

Recolonisation can only be successful if the threats which drove the species to extinction previously are either completely eliminated or significantly reduced. So Yadav and his colleagues aim to work with local people, herders and conservation area management committees to change their attitudes towards the dogs and teach them the ecological importance of the species. Top predators play an important role locally and ultimately their return will benefit the environment for everyone – including the herders.

Yadav will start to put in place conservation initiatives targeted to reduce human-wild dog conflict through innovative interventions. These include setting up a livestock insurance scheme so that community members can claim compensation when they do lose any animals. And putting up fox lights to deter the wild dogs attacking livestock at night. The dogs are returning to the area because there is sufficient wild prey now. Yadav and his team plan to help the local community take the right steps to ensure that as the dogs return, they predate wild animals and not livestock, meaning locals are happy to live alongside them again.

Thank you to all our donors who helped us fund this work. You can help us support more projects like this with a donation today: