A personal account from the moors by Carlos Bedson, whom we are funding to lead an in-depth study to understand the sustainability of the population of mountain hares in the Peak District. The results of Carlos’s studies will help to provide advice crucial to saving our last wild mountain hares, and identify the most important population parameters to be prioritised for future hare re-introductions.

Thermal imaging

I recently heard on Radio 4 a repeat of a fascinating “The Living World” documentary from 2005 which featured the late Professor Derek Yalden describing the challenges of observing mountain hares in the Peak District.

Because mountain hares are nocturnal, they are mostly dormant, hiding amongst vegetation by day, which makes it difficult to find them and figure out how many there may be. At the end of the radio show Derek articulates his unfulfilled dream of being able to go out at night and see what the mountain hares are really doing.

Indeed we do know that these mountain hares in the Peak District are the only such animals in England and isolated from their Scottish counterparts by over 200 miles, meaning there is no inward migration, making them vulnerable to extinction.

The last attempts to count the mountain hares were in the early 2000s. Since then, without exception, every expert who knows the Peak District moors well, be they environmental science officer, land owner, game keeper, ranger or mountain leader guide, has said the same thing to me: the mountain hares are in decline.

The last attempts to count the mountain hares were in the early 2000s. Since then, without exception, every expert who knows the Peak District moors well […] has said the same thing to me: the mountain hares are in decline.

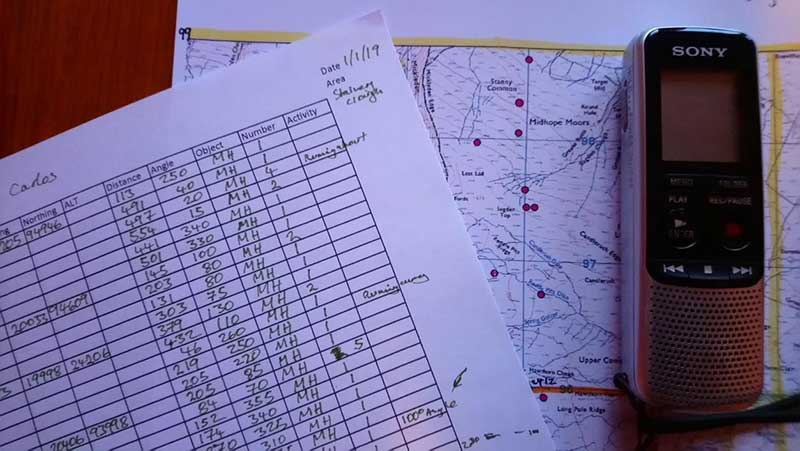

Therefore during my PhD studies, I have firstly been conducting distance sampling to try to achieve new estimates of abundance of mountain hares. This is a well-recognised method of walking transects and measuring distance and angles to survey animals, then using complex robust statistical analysis to ascertain numbers. The method works very well, yet for mountain hares can sometimes be hampered by their daytime hiding behaviour and tendency to flush at very short distances, making the statistical modelling difficult.

In addition, a further challenge I have noticed, is that by day mountain hares are seen less frequently upon the grouse moors and the young pioneer heather areas, whereas the pellet counts on the ground in these places indicate mountain hares visit them frequently at night. Therefore day time observations may suggest resting locations and not be representative of where mountain hares are nocturnally active. By comparison, European brown hares are known to travel up to 2km to their nightly feeding grounds. So another question is: do mountain hares hide somewhere high up on the hill by day and come down to the grouse moors at night?

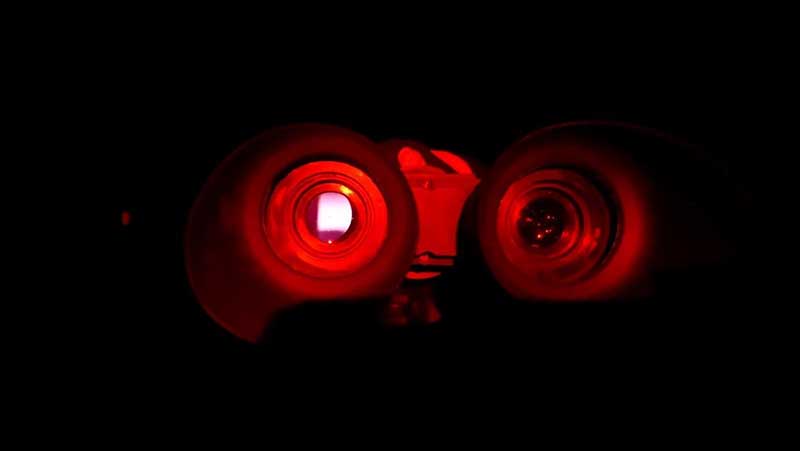

I feel very fortunate to be using what is one of the most advanced pieces of night detection equipment in the world.

In 2018 we determined to answer some of these questions with the help of a high powered thermal imager. It is poignant to listen to that Living Word radio programme and hear Derek Yalden, an incredible natural historian, who spent nearly 40 years surveying Peak District mountain hares, express this was the very device he was longing for.

Mordor or Moor?

I feel very fortunate to be using what is one of the most advanced pieces of night detection equipment in the world, to gaze upon the heat radiation signatures from mountain hares. This device has been obtained with the support of People’s Trust for Endangered Species and the Hare Preservation Trust, both very considerate discerning charitable organisations which are leading the way in supporting scientific research on these vulnerable lagomorphs.

A bit like what Frodo Baggins sees when he puts on the ring of power in The Fellowship of the Ring.

The thermal imager works by interpreting heat radiation and then projecting this on to an internal screen. At night everything becomes crystal clear and using a white on black viewing parameter, the moorland habitat is rendered like a negative photograph image, or I like to think, a bit like what Frodo Baggins sees when he puts on the ring of power in The Fellowship of the Ring.

By day mountain hares are hiding and at the first sign of a human being, they will bolt away at 40 mph never to be seen again. However at night, mountain hares believe they cannot be seen: they display little or no evasive behaviour. I have stood watching them with the thermal imager at a distance of 30 metres and they feed, frolic or amble around me, feeling confident and safe. This is tremendously helpful. I get a much better and ecologically authentic impression of where the hares are, how many occur in groups, how far apart they are from each other.

When I go out at daytime, I might see 1 to 4 hares per kilometre that I walk. However with the thermal imager I can see many more – sometimes four times as many. They are no longer hiding; they are active. Some are congregating in groups on heather burns, feeding together for predator vigilance. This might make me think that there are bunches of hares everywhere. However, I also measure the distance to these groups and between them. The thermal imager is amazing because it lets me see mountain hares sometimes out to 1,000 metres range. Yet there are sometimes big gaps in between, so whist I may get up to 10 or 20 detections from a vantage point, these mountain hares may be very widely spatially distributed.

Thermal imaging is thermal suffering

Sometimes I am out there at minus 10 or even colder […] I have to go out in what is literally a Polar expedition down jacket, to allow me to operate and survive several hours of standing still at these extreme temperatures.

The other thing that I of course notice (and suffer) is that it is extremely cold on the moors. Sometimes I am out there at minus 10 or even colder. And what amazes me is that the mountain hares do not care. They scamper out regardless of the temperature. Their fur coats are absolutely amazing in protecting them from such severe temperatures. And fortunately it still releases heat, allowing me to see their thermal signatures.

So there is a human side to this observation work too. Certainly I have to go out in what is literally a Polar expedition down jacket, to allow me to operate and survive several hours of standing still at these extreme temperatures.

I then suffer from Reynaud’s disease, meaning at low temperatures my fingers turn white, painful, numb and useless, so I have to keep my hands in thick mittens, with handwarmers inside. I also quickly sustain painful chill blains in my toes, so recently I have been putting handwarmers inside my boots, too.

And also – the thermal imager – it too cannot operate well in the cold. So I have to wrap it up in a sock, with a handwarmer strapped to the battery casing, to allow its power source to eke out for a few more minutes.

The thought of falling into a pool of icy bog water at midnight, far from help, fills me with dread.

Walking around on the peat bog landscape at night is rather grim. Sometimes there are marshes, pot holes and treacherous ice surfaces with deep water below. The thought of falling into a pool of icy bog water at midnight, far from help, fills me with dread and knowing my body’s own cold intolerance, I wonder I might possibly not enjoy the experience. I tread carefully. Fortunately nothing has happened so far. The worst nights I have known were during March 2018, when there was deep snow upon Holme Moss. One night tramping through the thigh deep snowdrifts, it took me 2 hours to travel 1500 metres. It felt perhaps a little like Scott of the Antarctic. The mountain hares, by contrast, were not bothered.

I have many more nights to spend on the moors, to achieve thorough and robust coverage of the various habitat types the mountain hares occupy in the Peak District. Once done, I shall be spending cosy days indoors, examining the observation records and contrasting them with those I have obtained at the same locations during the day. This may be used to create comparative descriptions of mountain hare distribution and numbers.

Given everyone says the mountain hares are in decline, this information is sorely needed. The observations of mountain hares I record with the thermal imager will provide a unique insight to where these animals are roaming, feeding and socialising by night. This is the view behind the curtain of darkness that Derek Yalden longed for in 2005. I feel privileged to be able to hold a candle to his dream.

Written by Carlos Bedson, PhD Researcher at Manchester Metropolitan University.

£30 can supply Carlos with a camera trap to help him monitor the mountain hares much more efficiently. Can you help?